E-commerce Waste and the Business of Plastics Incineration in Mexico City

3 de October de 2024

Translated from Spanish

Although most states in Mexico have implemented laws banning single-use plastics, the growing e-commerce boom following the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a loophole in these regulations. In Mexico City (CDMX), where 30% of the country’s e-commerce consumers are concentrated, packaging plastics used by platforms like Amazon and Mercado Libre are still not explicitly banned. The problem is that this waste is not recycled, but rather transported to private plants where it is incinerated, generating microplastics and releasing polluting gases. Contracts obtained by Empower reveal that the only company authorized to incinerate CDMX’s waste is a subsidiary of CEMEX, which was paid over 389 million pesos (approximately 20 million USD) for its services between 2019-21.

By Elizabeth Rosales

The 2018 ban on plastic bags in states such as Sonora, Veracruz, and Quintana Roo1“¡Más verdes! Estos estados prohíben los plásticos de un solo uso,” Milenio, 11 June 2022, www.milenio.com/estados/que-estados-ya-aprobaron-prohibir-los-popotes-y-bolsas-de-plastico. triggered a domino effect that, to date, has led 29 federal entities2“¿Cuáles son los estados con leyes que prohíben el uso de plásticos?,” Diario del Sur, 3 July 2024, www.diariodelsur.com.mx/doble-via/cuales-son-los-estados-con-leyes-que-prohiben-el-uso-de-plasticos-12183604.html. to adopt similar legislation, including Mexico City in 2019. However, the fight to eradicate single-use plastics — those that are neither reused nor recycled — remains far from over.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, a new challenge to this fight emerged: plastic waste associated with e-commerce, a term referring to online shopping platforms, such as Amazon, Mercado Libre, Shein, and Aliexpress, among others.

Through them, anyone with internet access and a credit or debit card can order from thousands of products without leaving their home.

Following the pandemic, the use of these platforms surged worldwide, especially in Mexico. Here, this type of commerce quadrupled,3“E-commerce se cuadruplica respecto a antes de la pandemia: Llega a 658.3 mil mdp en 2023,” El Financiero, 28 February 2024, www.elfinanciero.com.mx/empresas/2024/02/28/ecommerce-se-cuadruplica-respecto-al-antes-de-la-pandemia-alcanza-los-6583-mil-mdp-en-2023. positioning this country as number one in e-commerce growth,4“Estudio sobre Venta Online en México – 2024,” AMVO, 2024, www.amvo.org.mx/estudios/estudio-sobre-venta-online-en-mexico-2024. according to the Mexican Association of Online Sales (AMVO).

The problem is that every time we make an online purchase, the use of plastic packaging increases. For example, bubble wrap is often used to fill empty spaces in boxes that are larger than the product being shipped or to cushion impacts, even for items that do not require it.

And in Mexico, the federal entity that receives the most of these plastics is the capital, Mexico City or CDMX.

About 30% of the country’s e-commerce customers live there, according to estimates by Oceana, an international ocean conservation organization that advocates for the elimination of plastics worldwide.

Nancy Gocher, senior campaigner and advocacy director at Oceana Mexico, sees this as a major issue because e-commerce plastics are neither recycled nor processed in an environmentally friendly way. Instead, they end up in open-air landfills where they break down into microplastics, or in incineration plants where they release harmful gases into the air, polluting the capital and surrounding areas.

Currently, the only company authorized to co-process Mexico City’s waste is Pro Ambiente, S.A. de C.V., a subsidiary of CEMEX, S.A.B. de C.V. (BMV:CPO, NYSE:CX), which operates a plant in Tepeaca, Puebla and another in Tlanepantla, State of Mexico. Between 2014-21, these plants received nearly 2 million tons of waste destined for incineration.

“Neither of these options is ideal,” said Gocher, referring to the fate of these plastics in both incineration plants and landfills. She emphasizes that plastics remain one of the world’s leading pollutants, impacting oceans, as well as human and animal health.

In February of this year, Oceana advocated for a reform to Mexico City’s Solid Waste Law to prohibit the use of single-use plastics in e-commerce, unless they are compostable, and to establish penalties for companies of up to 217,140 MXN for non-compliance.

However, the initiative was not passed in time by the Mexico City Congress and the legislators in charge of doing so left office on August 31 due to a change of legislature. Now, Oceana will have to resubmit this initiative and seek the support of the new congress.

The issue is that e-commerce benefits from a legal loophole in Mexico City, as current local laws do not explicitly prohibit single-use plastics for this purpose, even though the same material was banned along with plastic bags in 2019, Gocher explained.

No authority has precise data on the volume of plastics generated by this activity, but Oceana estimates that, in 2021, e-commerce produced 86,000 tons of plastic waste in Mexico City alone, equivalent to 29 garbage trucks full of plastic each day.

“What’s happening with these types of products is very serious and, certainly, effective legislation needs to be created and properly enforced,” Gocher said.

The cycle of single-use plastics

In Mexico City, the borough offices and two state government departments share responsibility for waste management, including plastics. On the one hand, the 16 boroughs of CDMX are responsible for collecting waste from their residents and transferring it to one of the 12 transfer stations overseen by the Secretariat of Works and Services (SOBSE).

At these stations, collection vehicles concentrate the waste so that larger capacity vehicles can pick it up and transport it to one of the four waste sorting plants, also operated by SOBSE. At these plants, waste is sorted and separated by type of material for final processing.

Plastics that are not recyclable, such as those from e-commerce, are taken to co-processing sites where they are incinerated.

In addition to the borough offices and SOBSE, Mexico City’s Secretariat of the Environment (SEDEMA) is responsible for developing, implementing, and evaluating environmental policies.

In line with these responsibilities, SEDEMA prepares an annual report called the Inventario de Residuos Sólidos (Solid Waste Inventory), which provides data on waste generation and management in CDMX based on indicators from the borooughs and SOBSE.

The most recent inventory contains data from 2022 and does not provide figures to confirm whether or to what extent the 2019 reform succeeded in reducing the generation of single-use plastics in CDMX.

Getting this kind of data is a complex matter, according to Claudia Hernández Fernández, general director of Environmental Policy and Cultural Coordination at SEDEMA, who responded to a written questionnaire sent by Empower via email.

This public official believes that the 2019 reform has led to a decrease in plastics generation, but acknowledges that measuring this is one of SEDEMA’s biggest challenges, as “it requires the active participation of all sectors involved,” such as the 16 boroughs and SOBSE.

For this article, Empower requested an interview with the communications department of SOBSE, but, by the time of publication, it had neither granted the interview nor responded to a written questionnaire.

Hernández explained that SEDEMA has promoted different strategies aimed at reducing plastics pollution and increasing circularity in the sector, referring to a “circular economy” model, which focuses on giving waste a second life.

However, she notes that this is only possible for certain plastics, such as those made from monomaterials (a single type of plastic) and reusable or recyclable plastics like PET.

“Single-use plastics cannot comply with these principles because they are designed for short-term use, becoming waste almost instantly,” the public official explained.

This is why these materials, when they reach the waste separation plants, are typically sent to co-processing or waste incineration plants, in accordance with Mexico City’s environmental standard on waste (NADF- 024-AMBT-2013).

Currently, CEMEX’s subsidiary — Pro Ambiente, S.A. de C.V. — is the only company authorized to perform co-processing for CDMX. It operates a plant in Tepeaca, Puebla and another in Tlalnepantla, State of Mexico.

For its services between 2019-21, CDMX paid Pro Ambiente a total of 389,065,973 MXN (equivalent to 20,190,242.50 USD5“Portal del mercado cambiario,” Banco de México, 19 September 2024, www.banxico.org.mx/tipcamb/main.do?page=tip&idioma=sp.), according to contracts obtained by Empower.6Freedom of information request with folio 090163122001631, Plataforma Nacional de Transparencia, 7 October 2022, buscador.plataformadetransparencia.org.mx.

The Tepeaca plant incinerates about 763 tons of waste per day from all transfer stations in Mexico City. In contrast, the Barrientos plant in Tlanepantla receives waste only from a sorting plant in Azcapotzalco. The Tepeaca plant has been involved in several controversies, including contaminating agricultural land, depriving rural residents of water, and failing to pay land use and property taxes.

Empower requested comments from both CEMEX and Pro Ambiente via email and social media. However, neither responded by the time of this publication.

Environmental conflicts due to waste incineration

In 2019, the CEMEX plant in Puebla was closed for failing to comply with federal environmental regulations by not detailing its harmful effects on the environment.7“Se cumplen cinco días de la clausura de Cemex; la empresa no tramitó licencias ni impacto ambiental,” La Jornada Oriental, 15 November 2019, www.lajornadadeoriente.com.mx/puebla/se-cumplen-cinco-dias-de-la-clausura-de-cemex-la-empresa-no-tramito-licencias-ni-impacto-ambiental. By that time, the plant had become the subject of 37 complaints filed with the Federal Attorney’s Office for Environmental Protection (PROFEPA), none of which resulted in irregularities or fines.8Freedom of information request with folio 330024422001477, Plataforma Nacional de Transparencia, 2 November 2022, buscador.plataformadetransparencia.org.mx.

According to PROFEPA, the only fines for environmental emergencies registered against CEMEX or its subsidiary Pro Ambiente, S.A. de C.V., between 1996 and 2022, were imposed in Coahuila in 1997, without specifying the amount; in Nuevo León in 2004, with a fine of 23,751 MXN; and in Tamaulipas in 2015, without detailing the amount.

The Tepeaca plant is still operational today, but 2019 was the last year it reported its hazardous waste discharges to the Mexican Pollutant Release and Transfer Registry (RETC),9“Registro de Emisiones y Transferencia de Contaminantes”, Semarnat, 24 January 2024, www.gob.mx/semarnat%7Cretc/articulos/registro-de-emisiones-y-transferencia-de-contaminantes. an environmental policy instrument – whose participation is voluntary for companies – that collects data on toxic substances released into the environment.

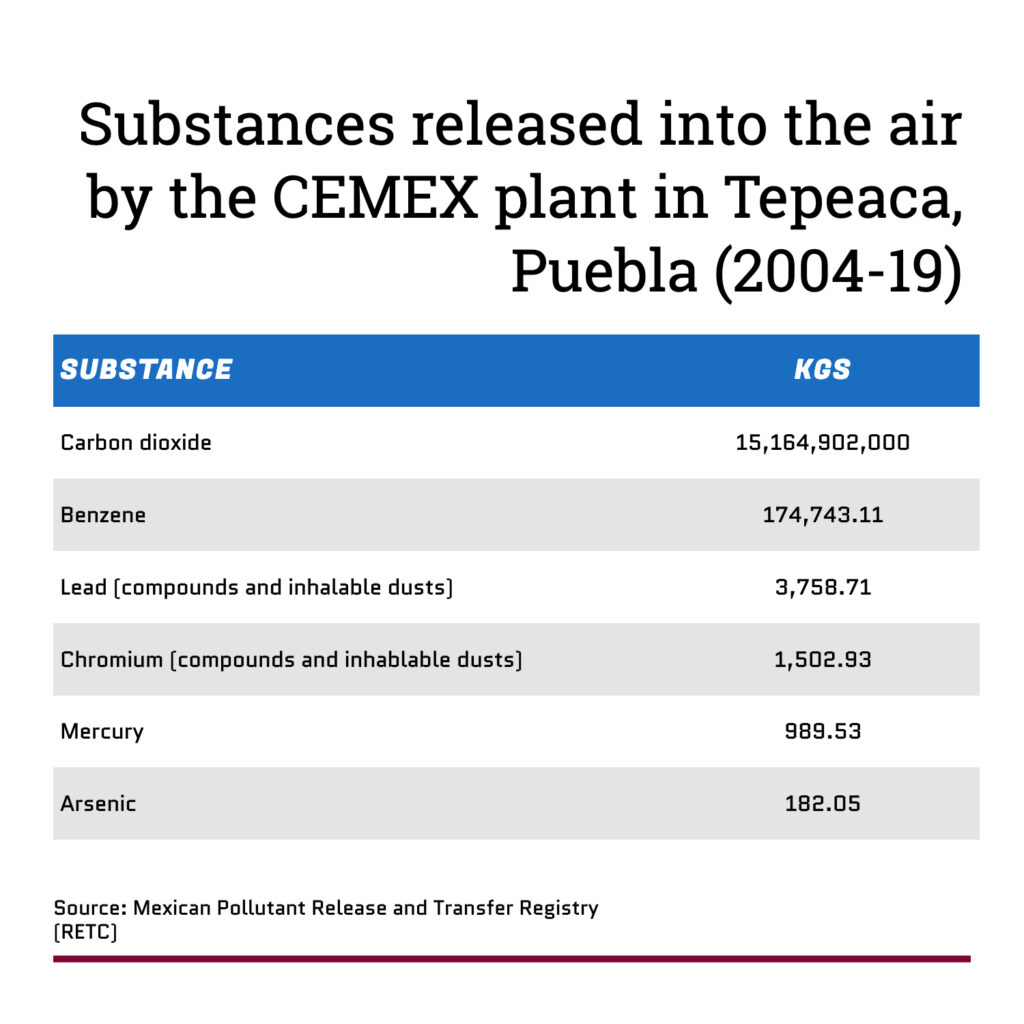

According to record CME732104011, the CEMEX plant in Tepeaca reported nine substances released into the air between 2004-19.

In addition to the pollution caused by waste incineration, media outlets such as La Jornada de Oriente10“Se dispara en 700% especulación inmobiliaria en torno a la ampliación de Cemex en Tepeaca,” La Jornada de Oriente, 17 February 2020, www.lajornadadeoriente.com.mx/puebla/se-dispara-en-700-especulacion-inmobiliatria-en-torno-a-la-ampliacion-de-cemex-en-tepeaca. have reported that “uncontrolled” water extraction by CEMEX has caused havoc in the region’s agricultural communities.

CEMEX, located in the municipalities of Cuautinchán, Tecali de Herrera, and Tepeaca, Puebla, holds five water concessions that allow for the extraction of 1,611,008 m3 of groundwater per year and a discharge volume of 25,455 m3 of wastewater annually, according to the Public Registry of Water Rights (REPDA). This is equivalent to 53 million 30-liter water jugs per year or, put differently, 147,124 jugs per day.

Additionally, other journalistic allegations against CEMEX11Miguel Barbosa, “CEMEX no ha mostrado disposición para resolver conflictos en Cuautinchán y Tepeaca,” El CEO, 2 October 2020, elceo.com/negocios/cemex-no-ha-mostrado-disposicion-para-resolver-conflictos-en-cuautinchan-y-tepeaca-miguel-barbosa. stand out, such as the claim that, in 2020, CEMEX owed 120 million MXN in property taxes to the municipality of Cuautinchán, despite supplying materials to projects such as the Dos Bocas refinery in Tabasco, the “Maya” train in the Yucatán Peninsula, and the Felipe Ángeles airport in the State of Mexico.

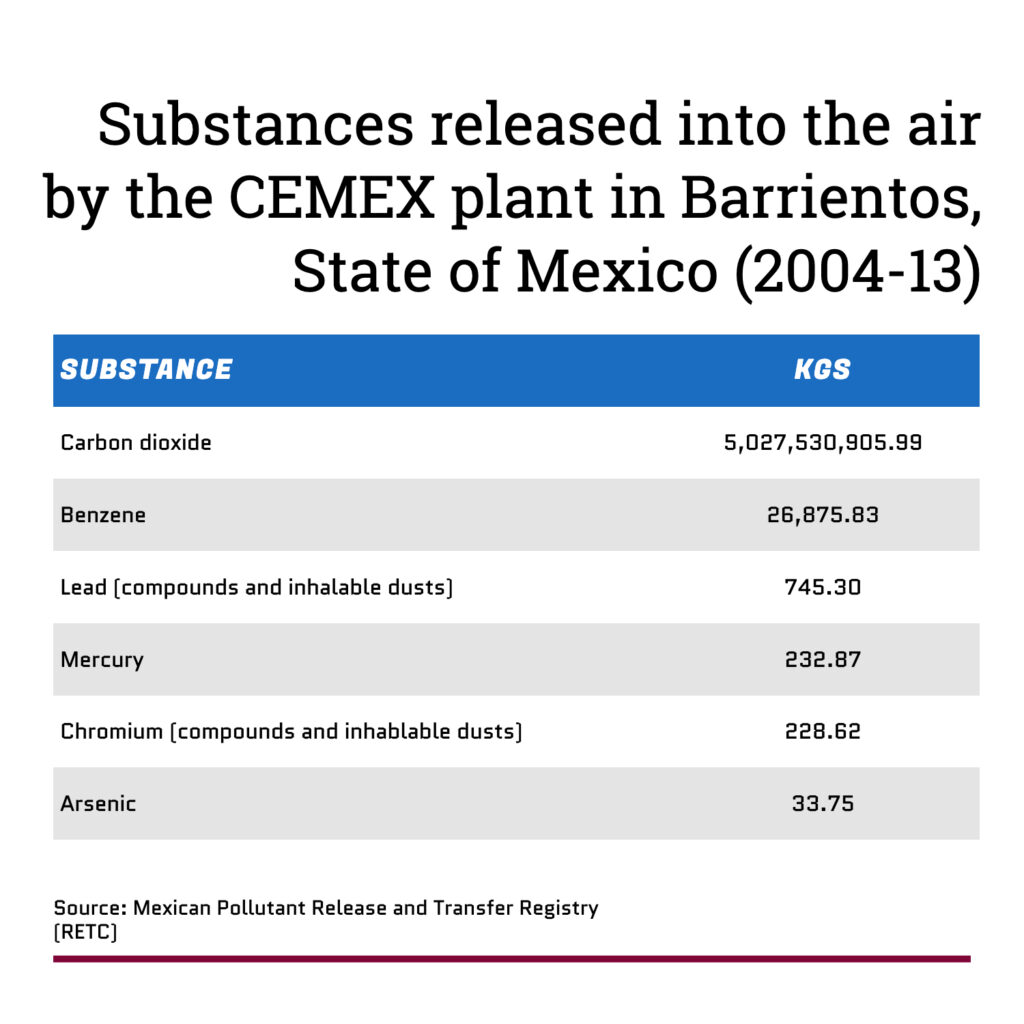

As for the emissions from the CEMEX plant in Barrientos, State of Mexico, it has not submitted reports to the RETC since 2013 and the only available data on its environmental impacts are as follows:

Waste management challenges

Proposing a solution to the problem of single-use plastic pollution is challenging, even for experts such as Alethia Vázquez, a research professor at the Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana (UAM) in Azcapotzalco and a specialist in plastic waste.12“Dra. Alethia Vázquez Morillas – Currículum Vitae,” UAM Azcapotzalco, 16 April 2024, dcbi.azc.uam.mx/media/ConsejoDivisional/Sesiones/Sesion708/2.3_Consejo_DCI_testado.pdf.

On one hand, she notes the limitations in the lack of official data available to understand the specific type of pollution being generated in the city.

“We [at UAM Azcapotzalco] have taken on the task of generating this information, but I believe the authorities lack the necessary human and financial resources to carry out these tasks,” explains Vázquez, who believes that the largest source of plastic pollution continues to come from plastic bags, Styrofoam, and disposable items.

From her point of view, the lack of data has to do with the fact that waste management depends on two separate entities (SEDEMA and SOBSE) that rely on 16 borough offices, and that each Secretariat faces different problems so that they do not always act as one.

“There are policies that were developed by SEDEMA that the SOBSE is not implementing because it has to prioritize operations, such as ensuring that garbage trucks collect waste daily to prevent a public health or social issue. So I believe that sometimes they are not exactly aligned, perhaps not due to a lack of willingness but rather to budget constraints and a lack of technically trained personnel,” says Vázquez.

Regarding the plastics generated by e-commerce, Vázquez points out challenges starting with waste separation, explaining that while some packaging plastics could be recycled, this doesn’t happen in practice because it is not profitable for waste separators to sell them by the kilo.

“People are paid per kilo of material and, in order to collect a kilo of bottles, a person may need to bend down 20 or 30 times to pick them up. In contrast, to gather a kilo of e-commerce packaging bags, it takes over a hundred such astions, so the cost-benefit ratio is not convenient for these people,” explains the researcher. “It is also not easy to think of substitutions [for e-commerce]. Compostables are more expensive and, well, there’s the issue of counterfeit products, plastics that claim to be compostable but aren’t.”

According to SEDEMA, in CDMX there are 25 companies authorized to produce and sell compostable plastic bags, 49 companies for other compostable plastic products, 30 for reusable bags, 23 for bags for inorganic waste management, and 5 for plastic products made from post-consumer recycled material.

The 2019 reform and the legislative proposal in waiting

After the first states legislated in 2018 the ban on plastic bags in the country, Mexico City implemented a reform of its own that also included other products made with single-use plastics, including disposable utensils, tampon applicators, balloons, and plastic rods.

As mentioned, 29 states have adopted similar measures,13“¿Cuáles son los estados con leyes que prohíben el uso de plásticos?,” Diario del Sur, 3 July 2024, www.diariodelsur.com.mx/doble-via/cuales-son-los-estados-con-leyes-que-prohiben-el-uso-de-plasticos-12183604.html. but none have yet considered banning plastics from e-commerce.

Oceana decided to push for an initiative to ban these plastics in CDMX for two reasons: because this entity has the highest percentage of e-commerce users in the country, and because it saw an opportunity to start a cascade effect similar to what was seen with plastic bags.

“The impact that Mexico City could have, especially as an example for other states, would be very significant, which is why we decided to approach it this way,” said the spokeswoman for this organization.

It was in February of this year that deputies Javier Ramos Franco, from the Green Ecologist Party of Mexico (PVEM), and Federico Döring Casar, from the National Action Party (PAN), presented this initiative to regulate e-commerce waste before the local Congress, the same one that approved the 2019 anti-plastics reform.

“We had it on the agenda, so we approached Oceana, a very serious organization dedicated to protecting the oceans, with plastics as one of their focus areas. All this led us to elaborate and present this initiative that precisely tried to regulate other types of single-use plastics. At the time, we said it was the second phase of the major reform achieved in 2019 […] unfortunately, you know the results and, so far, we haven’t managed to gain traction with the proposal,” said deputy Ramos in an interview conducted on August 21, a week before the end of the II Legislature period.

The initiative was awaiting a ruling for a little over five months from the Environmental Commission, chaired by Deputy Tania Larios of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Finally, on July 31, an ultimatum was issued with a five-day deadline14“Congreso de CDMX da ultimátum a diputada del PRI,” Oceana, 31 July 2024, mx.oceana.org/comunicados/congreso-de-cdmx-da-ultimatum-a-diputada-del-pri. to deliver an opinion. However, the deadline expired without Larios convening a legislative meeting.

“Given that this Commission was either unwilling or did not have it on their agenda to address the analysis of this issue, it was requested that the matter be referred to another commission, as mandated by the internal regulations of the Congress,” Ramos explained at the time.

The initiative thus passed to the Committee on Legislative Regulations, Studies, and Parliamentary Practices, but again it was unsuccessful.

The term of that legislature ended on September 1 when the new congress took office, without the initiative promoted by Oceana obtaining a ruling. As a result, it will have to be resubmitted from scratch to the new legislature.

Amazon and Mercado Libre, the main shopping platforms in Mexico

Due to the lack of tools to measure single-use plastic pollution in Mexico, and even less so to track it, it is impossible to determine which e-commerce companies are the largest contributors to this type of pollution.

However, the most significant companies in this sector in Mexico, based on their market share in 2022, were Mercado Libre (24%) and Amazon (23%), far ahead of third place Walmart México (7%), according to Statista,15“Participación de mercado de las principales empresas del comercio electrónico en México en 2022,” Statista, 2022, es.statista.com/estadisticas/1114202/mexico-empresas-lideres-comercio-electronico-minorista. a statistics portal providing market research data.

The difference between Amazon and Mercado Libre is that Amazon concentrates its logistics operations in 11 distribution centers16“¿Cuántos centros logísticos tiene Amazon en México?,” The Logistics World, 18 November 2023, thelogisticsworld.com/logistica-comercio-electronico/cuantos-centros-logisticos-tiene-amazon-en-mexico. located in cities such as Tijuana, Monterrey, Guadalajara, and Mexico City, among others. Thus, Amazon is in charge of packaging and shipping, while in Mercado Libre the final person responsible remains the individual seller. According to researcher Alethia Vázquez, this would be difficult to monitor in the event that the use of plastics for e-commerce is regulated.

“A lot of attention is focused on Amazon, and it is clear why, but we have many other platforms where the situation is even more complex. For example, in Mercado Libre, shipping is done directly by the seller, but who is going to regulate the thousands of sellers in the country?,” she questioned.

Just in June of this year, Amazon announced its commitment to eliminate by 95% the use of bubble wrap in its packaging in North America in order to offer its customers a more sustainable experience. “This will be Amazon’s largest plastic packaging reduction effort in North America and will avoid nearly 15 billion plastic air pillows annually,” the platform announced in a press release.17“Amazon anuncia su mayor reducción de embalajes de plástico en Norteamérica,” Amazon, 20 June 2024, www.aboutamazon.com/news/sustainability/amazon-anuncia-mayor-reduccion-de-embalajes-de-plastico.

For Prime Day, which was July 16 and 17,18“When is Amazon Prime Day 2024?,” Amazon, 16 July 2024, www.aboutamazon.com/news/retail/amazon-prime-day-2024-date. Amazon claims to have fulfilled this commitment at least in the United States and, by the end of the year, expects this to be true for all of North America, including Mexico, Amazon spokeswoman Barbara Agrait told Empower.

According to Oceana’s Nancy Gocher, Amazon orders arriving from the United States are starting to reduce plastics in their shipments, but the packages that may not yet do so are those prepared in Mexican distribution centers.

The problem is that, in addition to Amazon, there are thousands of e-commerce platforms that have not made this commitment and it is not desirable to rely solely on the goodwill of companies.

“It is very difficult for companies to commit if there is no legislation in place, especially in Mexico, where commitments can be evaded at any time,” Gocher said.

Michelle Montiel, 30, a resident of Mexico City, uses these platforms up to eight times a month, with Amazon and Mercado Libre being the ones she uses the most. Her opinion is that both could improve their logistical efficiency in order to pollute less.

“I must admit that Amazon sometimes has this initiative that, if you order several things, they try to put them together so that there is only one package, but this is not always the case. In Mercado Libre, if you order three things, they can arrive on the same day but with three different delivery drivers and in three different packages,” says Montiel.

In her experience, she also notes that there are times when she places online orders and notices that the product does not justify the amount of plastic packaging. Sometimes she orders items such as toys or puzzles that wouldn’t suffer significant damage without bubble wrap or other plastics; however, she has found them when opening her packages.

Alejandro Coronado, 31, also a resident of Mexico City and an e-commerce user at least eight times a month, receiving up to 16 packages, tells a similar story.

“Sometimes they send me soap bars with excessive packaging or similar items, and I don’t think it makes sense for them to be so [protected], but on the other hand I understand. When I order an electronic device or something of higher value, I do think some kind of protection is necessary, and I would prefer that be the case,” says Coronado.

From his point of view, the environmental impact of buying a second cell phone because the first one was damaged during shipping may be even greater, but, in general, he thinks that protective packaging could be avoided for other types of products and, like Montiel, would prefer some measure to address this issue.

New congress, new opportunity

On September 1, the III Legislature19“Se instaló la III Legislatura del Congreso capitalino,” Congreso de la Ciudad de México, 1 September 2024, www.congresocdmx.gob.mx/comsoc-instalo-iii-legislatura-congreso-capitalino-5459-1.html. of the Capital Congress, comprised by 66 deputies, was installed. In the coming months, they will be responsible for evaluating Oceana’s initiative, issuing a ruling, and, if applicable, bringing it to the plenary for a vote.

Ramos Franco said in an interview that his party, as well as Oceana, will take up the issue again because it responds to a citizen demand and a need in the face of global problems such as microplastics and global warming.

Although in Mexico, e-commerce plastics are a topic that is just beginning to be discussed, countries like Colombia, Chile, China, and India have already passed legislation to eliminate them in their territories.

The global trends are worrisome for environmental advocates and this is why they persist in their advocacy demands. According to data from Oceana, the world’s annual plastic production increased from 1.8 million tons in 1950 to 465 million tons in 2018, and only 9% of all plastics ever produced in human history has been recycled.

In addition, for Mexico, projections suggest that 90% of the Mexican population will be e-commerce users by 2029, according to Statista.20“Porcentaje de compradores online sobre el total de la población en México de 2017 a 2029,” Statista, 2017-29, es.statista.com/previsiones/703404/tasa-penetracion-comercio-electronico-mexico. In this regard, Oceana does not consider asking users to stop shopping online as a viable option, but rather demands that large companies eliminate single-use plastics, as they have the economic and logistical capacities to switch from polluting materials, as well as the responsibility to act in the face of the plastic environmental crisis.

“What people can do is ask those companies not to use plastic and ask the authorities to create strong legislation so that they don’t have the possibility to use those plastics,” Gocher said.

Although they don’t know each other, but Michelle and Alejandro agree on this.

“It would be appropriate to force companies to find more sustainable alternatives. Times have changed and [e-commerce] has taken on a bigger role in everyone’s life,” said Montiel.

“I think it’s an immediate response to society’s demands. I don’t believe there are many people who are against regulation,” added Coronado. “I don’t feel like such regulation would be a problem for individuals, but it could be an issue for companies. If this gets regulated, it would clearly identify those responsible,” he concluded.

1 “¡Más verdes! Estos estados prohíben los plásticos de un solo uso,” Milenio, 11 June 2022, www.milenio.com/estados/que-estados-ya-aprobaron-prohibir-los-popotes-y-bolsas-de-plastico.

2 “¿Cuáles son los estados con leyes que prohíben el uso de plásticos?,” Diario del Sur, 3 July 2024, www.diariodelsur.com.mx/doble-via/cuales-son-los-estados-con-leyes-que-prohiben-el-uso-de-plasticos-12183604.html.

3 “E-commerce se cuadruplica respecto a antes de la pandemia: Llega a 658.3 mil mdp en 2023,” El Financiero, 28 February 2024, www.elfinanciero.com.mx/empresas/2024/02/28/ecommerce-se-cuadruplica-respecto-al-antes-de-la-pandemia-alcanza-los-6583-mil-mdp-en-2023.

4 “Estudio sobre Venta Online en México – 2024,” AMVO, 2024, www.amvo.org.mx/estudios/estudio-sobre-venta-online-en-mexico-2024.

5 “Portal del mercado cambiario,” Banco de México, 19 September 2024, www.banxico.org.mx/tipcamb/main.do?page=tip&idioma=sp.

6 Freedom of information request with folio 090163122001631, Plataforma Nacional de Transparencia, 7 October 2022, buscador.plataformadetransparencia.org.mx.

7 “Se cumplen cinco días de la clausura de Cemex; la empresa no tramitó licencias ni impacto ambiental,” La Jornada Oriental, 15 November 2019, www.lajornadadeoriente.com.mx/puebla/se-cumplen-cinco-dias-de-la-clausura-de-cemex-la-empresa-no-tramito-licencias-ni-impacto-ambiental.

8 Freedom of information request with folio 330024422001477, Plataforma Nacional de Transparencia, 2 November 2022, buscador.plataformadetransparencia.org.mx.

9 “Registro de Emisiones y Transferencia de Contaminantes”, Semarnat, 24 January 2024, www.gob.mx/semarnat%7Cretc/articulos/registro-de-emisiones-y-transferencia-de-contaminantes.

10 “Se dispara en 700% especulación inmobiliaria en torno a la ampliación de Cemex en Tepeaca,” La Jornada de Oriente, 17 February 2020, www.lajornadadeoriente.com.mx/puebla/se-dispara-en-700-especulacion-inmobiliatria-en-torno-a-la-ampliacion-de-cemex-en-tepeaca.

11 Miguel Barbosa, “CEMEX no ha mostrado disposición para resolver conflictos en Cuautinchán y Tepeaca,” El CEO, 2 October 2020, elceo.com/negocios/cemex-no-ha-mostrado-disposicion-para-resolver-conflictos-en-cuautinchan-y-tepeaca-miguel-barbosa.

12 “Dra. Alethia Vázquez Morillas – Currículum Vitae,” UAM Azcapotzalco, 16 April 2024, dcbi.azc.uam.mx/media/ConsejoDivisional/Sesiones/Sesion708/2.3_Consejo_DCI_testado.pdf.

13 “¿Cuáles son los estados con leyes que prohíben el uso de plásticos?,” Diario del Sur, 3 July 2024, www.diariodelsur.com.mx/doble-via/cuales-son-los-estados-con-leyes-que-prohiben-el-uso-de-plasticos-12183604.html.

14 “Congreso de CDMX da ultimátum a diputada del PRI,” Oceana, 31 July 2024, mx.oceana.org/comunicados/congreso-de-cdmx-da-ultimatum-a-diputada-del-pri.

15 “Participación de mercado de las principales empresas del comercio electrónico en México en 2022,” Statista, 2022, es.statista.com/estadisticas/1114202/mexico-empresas-lideres-comercio-electronico-minorista.

16 “¿Cuántos centros logísticos tiene Amazon en México?,” The Logistics World, 18 November 2023, thelogisticsworld.com/logistica-comercio-electronico/cuantos-centros-logisticos-tiene-amazon-en-mexico.

17 “Amazon anuncia su mayor reducción de embalajes de plástico en Norteamérica,” Amazon, 20 June 2024, www.aboutamazon.com/news/sustainability/amazon-anuncia-mayor-reduccion-de-embalajes-de-plastico.

18 “When is Amazon Prime Day 2024?,” Amazon, 16 July 2024, www.aboutamazon.com/news/retail/amazon-prime-day-2024-date.

19 “Se instaló la III Legislatura del Congreso capitalino,” Congreso de la Ciudad de México, 1 September 2024, www.congresocdmx.gob.mx/comsoc-instalo-iii-legislatura-congreso-capitalino-5459-1.html.

20 “Porcentaje de compradores online sobre el total de la población en México de 2017 a 2029,” Statista, 2017-29, es.statista.com/previsiones/703404/tasa-penetracion-comercio-electronico-mexico.