Renewable energy transition

Global warming. Melting sea ice. Rising sea levels. Once-in-a-century storms. Depletion of fossil fuel resources. We all know the signs of the climate crisis. But what about the corporate capture of the State within the energy transition? What are the challenges and gaps keeping us from achieving a just energy transition?

A big challenge wrought by the energy transition is its timing, which could potentially divide the environmental movement. On one hand, arguing that the planet cannot wait any longer, there is pressure on the energy transition to happen as quickly as possible. On the other hand, there is a tension between human rights advocates, workers, communities, climate activists, and policymakers about how to ensure a just transition for both people and planet.

In this milieu we find the corporations themselves, essentially split between those benefiting from fossil fuels, those seeking to benefit from renewable energy, those that hedge their bets on both, and the investors and financial institutions that benefit from it all.The logic of the corporate capture of the State, of course, is how to maximize private interests vis-a-vis the common good.

The “corporate energy transition” — as conceived by the Transnational Institute and Taller Ecologista — perceives the climate emergency as an opportunity for the accumulation of wealth as well as geopolitical hegemonic positioning. This perspective, supported by multinational corporations, States, multilateral institutions, and various organizations, exclusively focuses on a techno-economic approach as the “fastest” response to the urgency of the climate crisis. Thus, the corporate energy transition does not represent a paradigm shift but rather “an expression of the way in which the capitalist system attempts to capitalize on the energy and climate crisis for a new cycle of accumulation.”

Machinery, projects, and research stay controlled by or work in favor of multinational corporations or world powers, limiting the possibility of democratizing the use of energy and technology. In this manner, existing power relations and inequality remain untouched. Such a transition permits the continuing process of wealth and power accumulation through new extraction areas: “Thus, the corporate energy transition is based on the trivialized notion of ‘sustainable development’, on continuing on the path of limitless growth, exchanging fossil resources for renewables and high technology, without modifying the logic of capitalist consumption, nor questioning the distribution or access to energy of populations or citizen participation in decision-making processes.”

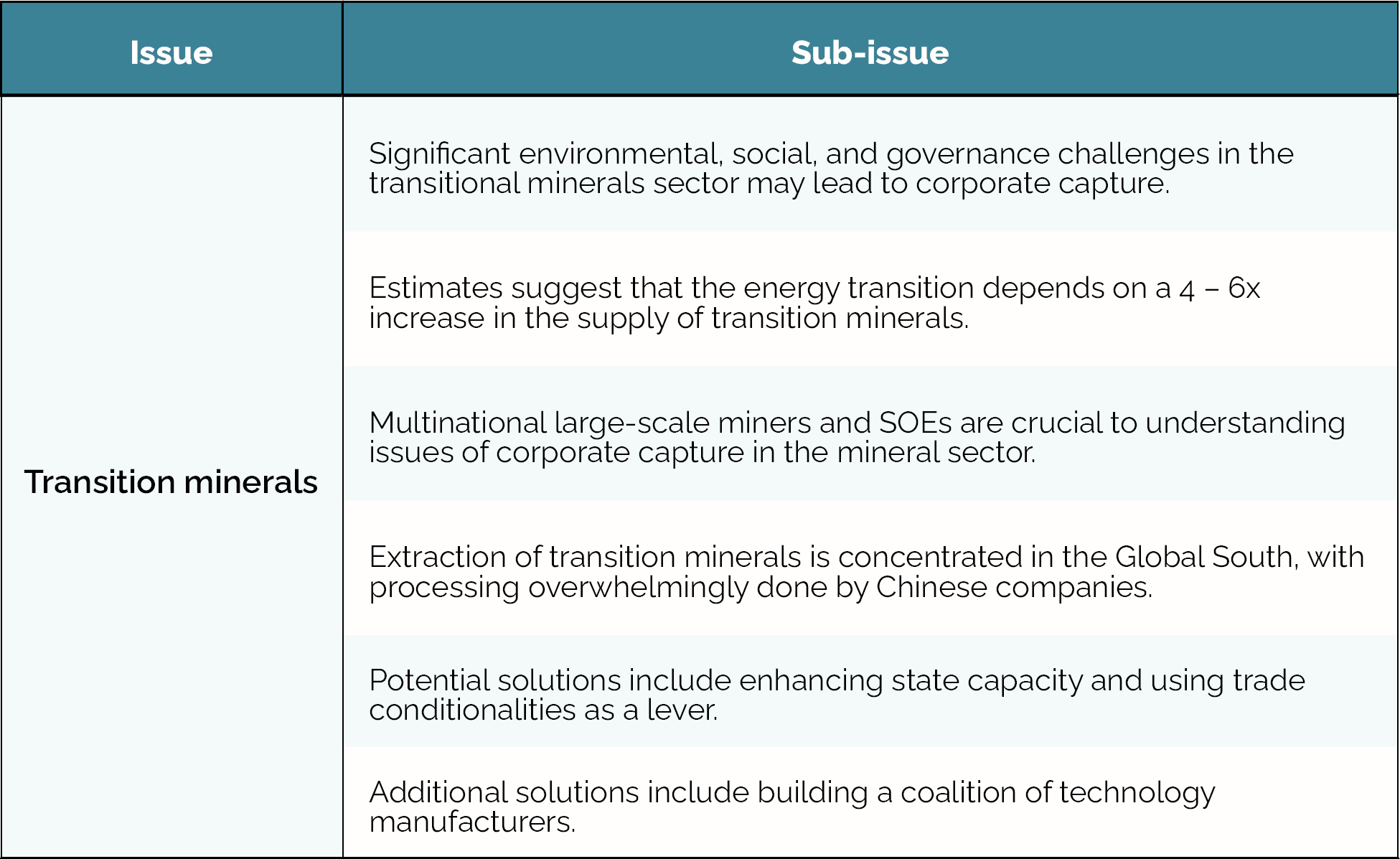

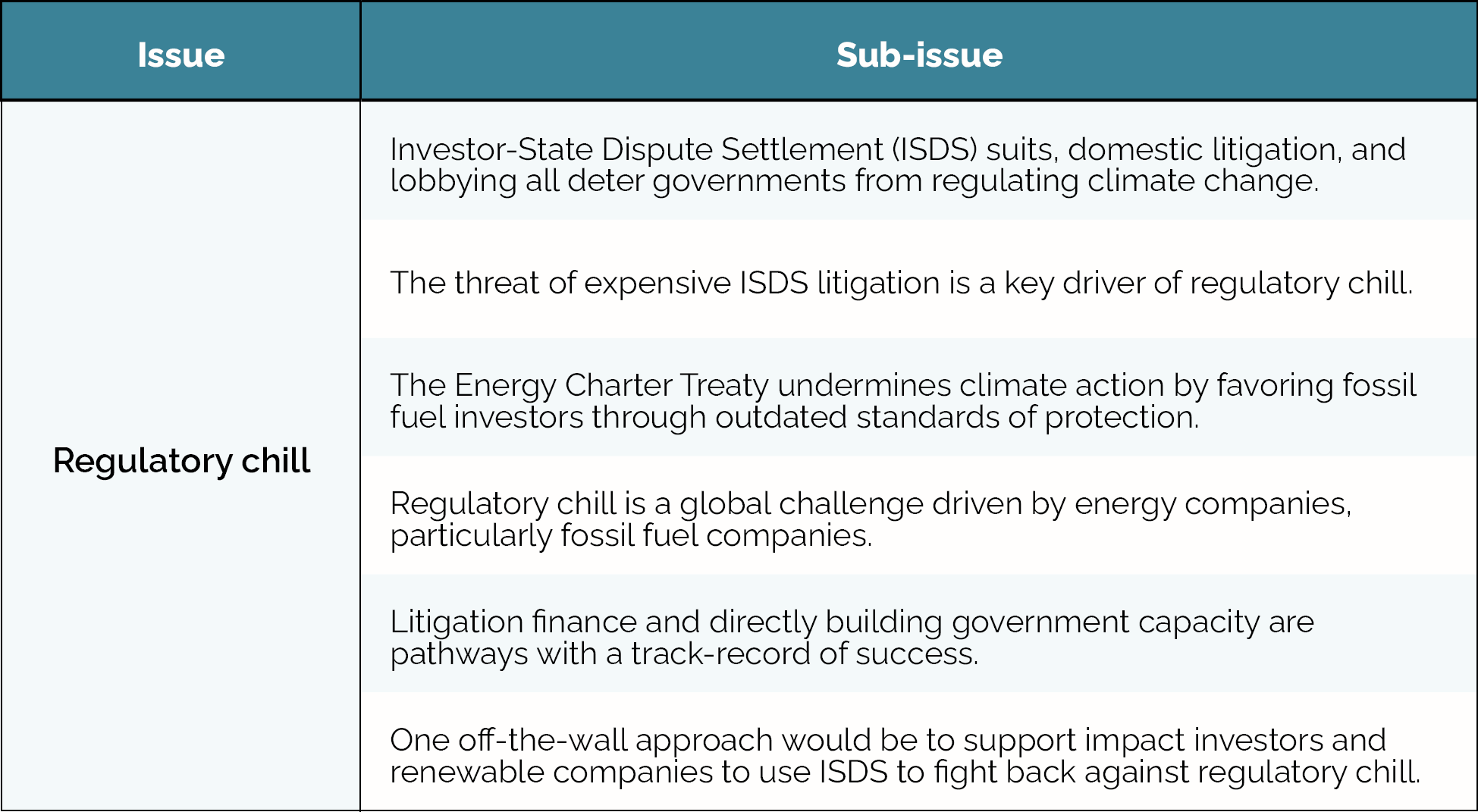

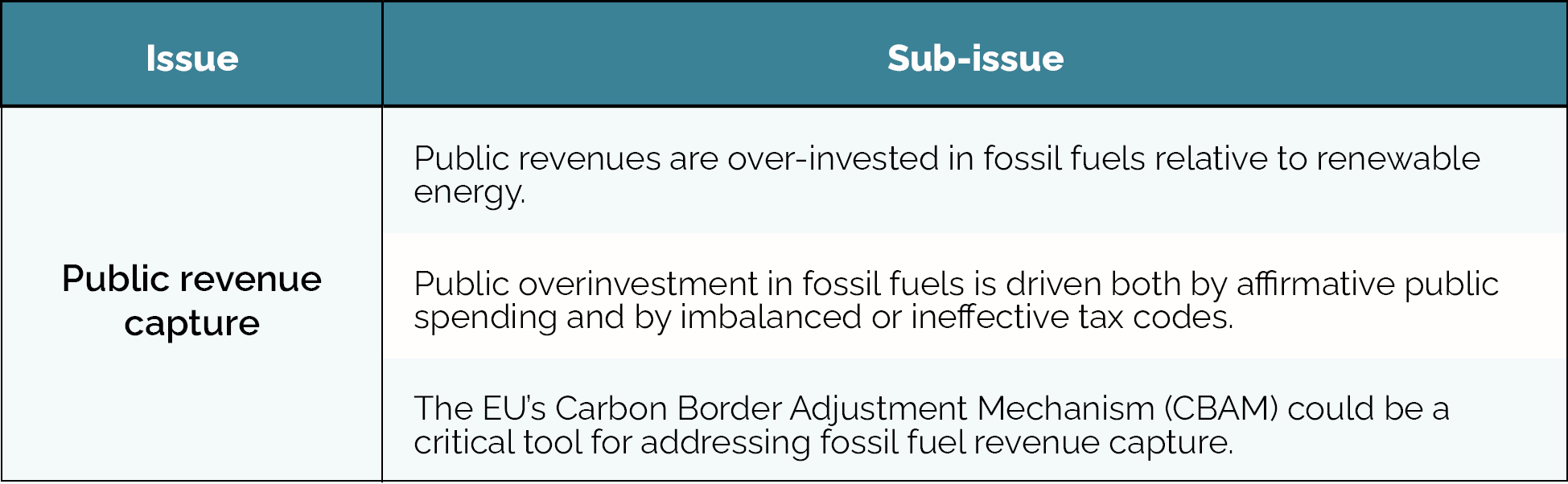

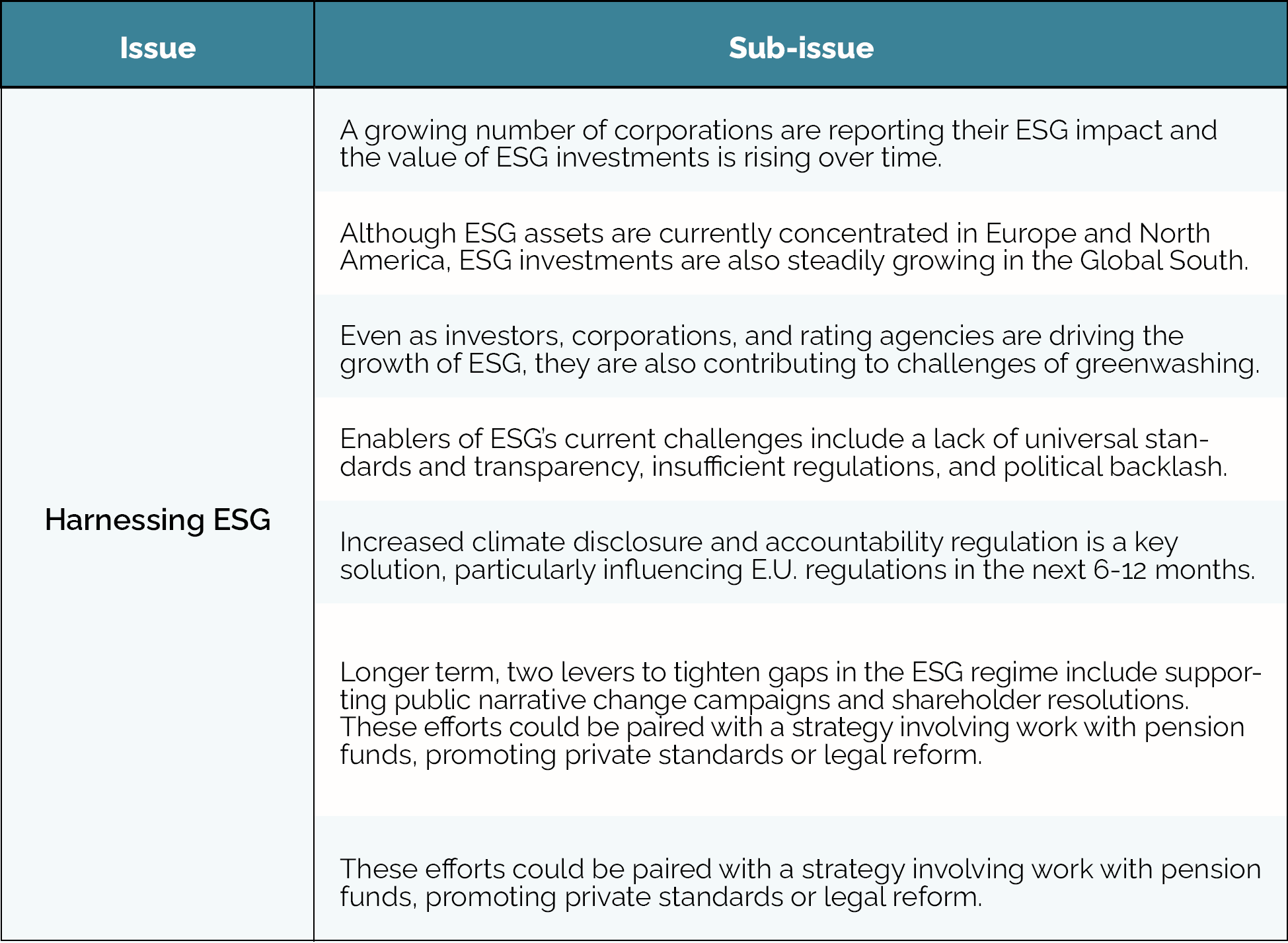

In June 2023, Dalberg, a strategy and policy advisory firm based in the Global North but with offices throughout the Global South, prepared a conceptual framework as part of a horizon scan on the climate and energy sector. We found it useful and have adapted it here as a guide for identifying the corporate capture challenges in the energy transition.

Dalberg describes many ofactors, interest, risk, and capture mechanismsin the energy transition. We complement its list as follows:

- Conceptual capture of renewables:Rhetorically, proponents of the renewal energy transition have used the term “green energy” almost to excess. The implication is who could possibly oppose “environmentally-friendly,” “green,” or “renewable” solutions. While partially true, this terminology has also caused harm. Some renewable energy companies, green developers, regulators, environmentalists, and journalists have taken this too far, having criticized, sued, attacked, and generally undermined their perceived opponents, including indigenous communities, rural landowners, human rights defenders, and workers whose rights, lives, and livelihoods are impacted by renewable energy development. This is problematic because there is an assumption that renewables are the solution, not the problem, so human rights violations committed by these companies are often minimized or overlooked. Conceptual capture, as it were, is baked into the solution.

- Corruption and undermining trust:Overall, one corporate capture strategy is simply to undermine the energy transition altogether. Fossil fuel companies and businesses dependent upon them are being disrupted at a ferocious pace. For many of them, the answer is to slow down the pace, including by facilitating corruption so as to cause States and the public to lose enthusiasm for the process. For example, “Corruption may undermine the effectiveness of [a] carbon tax and make it more difficult for the government to win public support to adopt ambitious policies, as [the] public may be less supportive of these policies if their adoption and specific characteristics are influenced by corrupt actors. (…) [The carbon] tax is susceptible to corruption and state capture risks at various stages of the policy cycle, including adoption, implementation, and evaluation.”

- Theft and diversion of resources:Just as with the energy transition from coal to oil and then to natural gas, States invest enormous amounts both upstream and downstream to facilitate development, creating incentives for private and public actors to commit theft and divert public resources. The renewable energy transition is no exception. “The most typical form of grand corruption occurring in renewables, based on existing research, is institutionalised grand corruption. (…) For example, there is evidence of institutionalised grand corruption in Malaysia through directing hydropower contracts to companies tied to the family of the chief minister of Sarawak, Mahmud Taib. (…) There are allegations of public spending for large dams being diverted to the Taib family, who remained in political power in the state of Sarawak, and to companies connected to this family.”