NOM-187 is shaping up to favor Maseca and Minsa

29 de September de 2022

Translated from Spanish

Since it was created in 2003 until some of its clauses were modified in 2013, the Official Mexican Norm (NOM, in Spanish) 187, which regulates the distribution, uses, and limits of nixtamalization, additives, naming, and distribution, among other things, of corn products in Mexico, partially benefited the interests of companies such as Maseca and Minsa. Today, on the eve of a new NOM-187 to replace the existing version from 2013, the Norm embodies a vision that favors industrial companies over local producers (tortilla and nixtamalization mills), as Empower discovered in the latest version of the document, which it obtained thanks to a leak. Currently, only the draft of NOM-187 has been made public because the final document has yet to be completed or published. This process has been on hold since the departure of Alfonso Guati Rojo as general director of Norms at the Secretary of the Economy (SE) in May 2022 and the subsequent arrival of Eduardo Montemayor Treviño to replace him.

By Claudia Ocaranza

”Our nixtamalization1According to National Geographic, nixtamalization is “ a process in which dried maize is soaked, then cooked in an alkaline solution that softens corn and renders it more digestible.”, Erin Blakemore, “Who were the Maya? Decoding the ancient civilization’s secrets”, National Geographic, 7 September 2022 www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/who-were-the-maya. process is more efficient in terms of water and energy consumption than the traditional method”2“Maquinaria,” Gruma, accessed 11 September 2022, www.gruma.com/es/innovacion/tecnologia/maquinaria.aspx. and “Maseca preserves the traditional nixtamalization process: specialists say”3“Maseca, conserva el proceso tradicional de la nixtamalización: especialistas,” Dinero en Imagen, 21 January 2020, www.dineroenimagen.com/empresas/maseca-conserva-el-proceso-tradicional-de-la-nixtamalizacion-especialistas/118952. are some of the messages that Maseca, a subsidiary of the Mexican conglomerate Gruma (BMV:GRUMA), a leader in the corn flour market, has generated since 1950 to convince both end consumers and its customers, small-scale tortilla factories, that its product follows the same process as nixtamalized corn masa and is the same or even better.

Today, that narrative, along with other factors such as the crisis facing small corn producers and nixtamal mills and the need for tortilla factories to generate more product at lower costs, has permeated the current process to create the new Official Mexican Norm 187 (NOM-187). According to sources involved, there has been little participation from traditional, small-scale companies in contrast to the over-representation of large industrial players and individuals simultaneously representing both companies and the interests of some of the country’s main industrial associations.

”We, the traditional industry, were given Maseca as a leader to follow, as if we couldn’t agree among ourselves, as if we didn’t know how to work together, but they need us because they (Maseca) don’t have direct points of sale,” Blanca Mejía, a representative of the Mexican Traditional Tortilla Governing Council in Mexico and founder of Corn Network who participated in the first stage of the current process to review and create the new NOM, told Empower.

In the latest version of the new NOM-187, dated May 28, 2022, which has not been approved or published (but to which Empower had access thanks to a leak), government agencies, civil society organizations, national and regional industrial associations, and companies appear as participants in the Working Group to draft the NOM-187. However, it is noteworthy that Gruma participated through several subsidiaries: Mission Foods México, Investigación Técnica Avanzada, Harina de Maíz de Mexicali, and Harina de Yucatán.

At least the first two Gruma subsidiaries submitted comments for the review of the norm, according to meeting minutes and observation tables that Empower reviewed. Moreover, the meeting minutes included people who have a dual role as industry representatives in some of the meetings and as company representatives in others. This is the case of Zully Corona Zurita, who attended the first meeting as the head of Bimbo and, later, another meeting as part of the National Agricultural Council (CNA).

Another source, who requested anonymity because they still participate in the process, confirmed that the over-representation of large industrial companies impacted how some specific issues were raised, such as the definition of nixtamalization and its denomination (what is reported to consumers about corn products).

Traditional versus industrial nixtamalization

The latest non-public version of the NOM in revision defines nixtamalization as the ”process of cooking corn in water with calcium hydroxide and then subjecting it to a soaking period for the purpose of obtaining corn nixtamal that can be ground to dough or ground and dehydrated to flour.” Although this marks an improvement compared to the original definition of the first NOM-187, created in 2003, where there was no mention that the corn with calcium hydroxide must be soaked, the latest definition still falls short of protecting corn mills and those who make nixtamal in the traditional style.

The soaking period is key in order for corn to retain its benefits and not require added minerals, nutrients, and vitamins, which Maseca and Minsa (BMV:MINSA) do add to their corn masa. This additional step, which authorities require of the large companies, is promoted as a competitive advantage, according to nixtamal producers consulted by Empower.

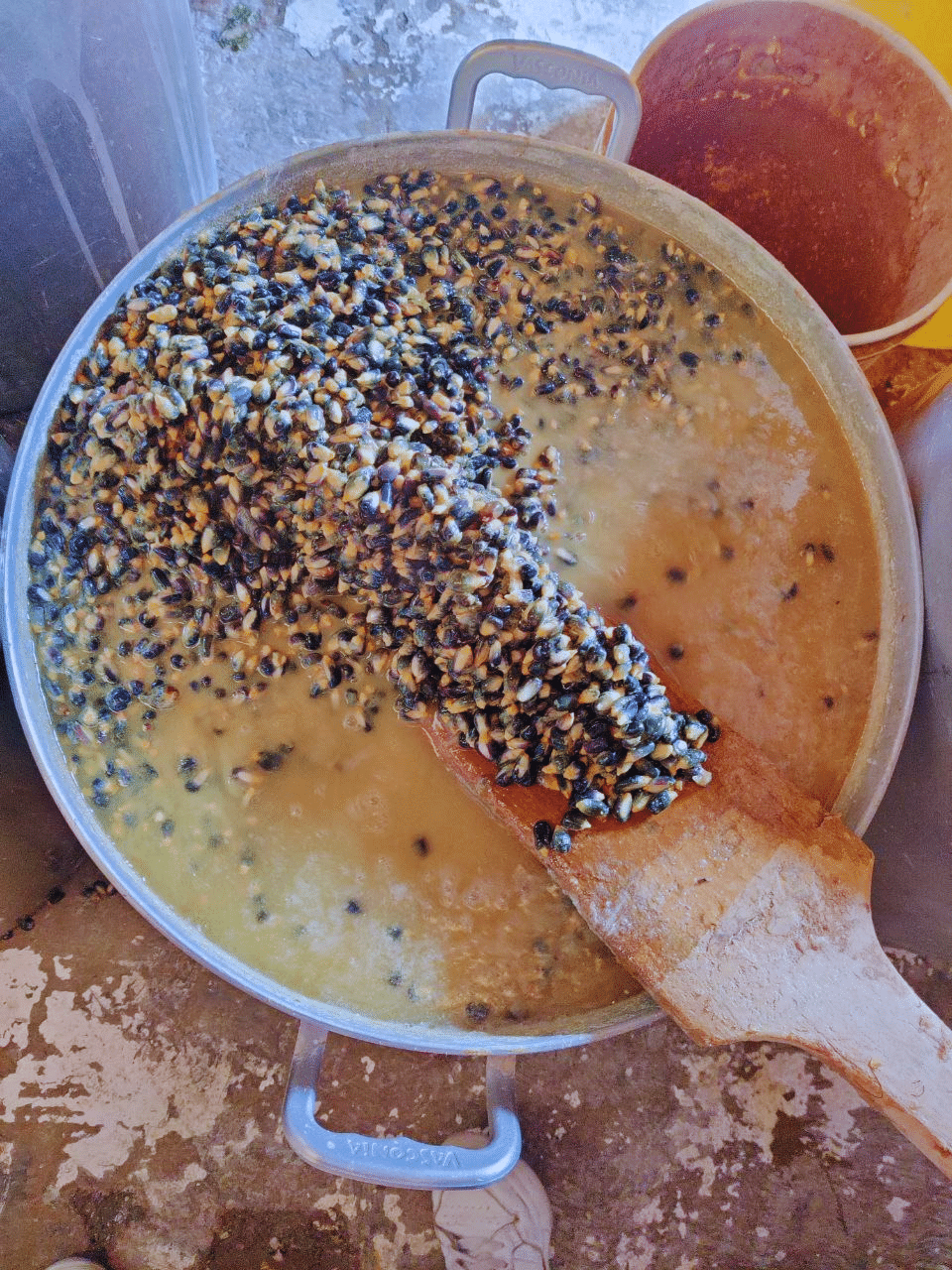

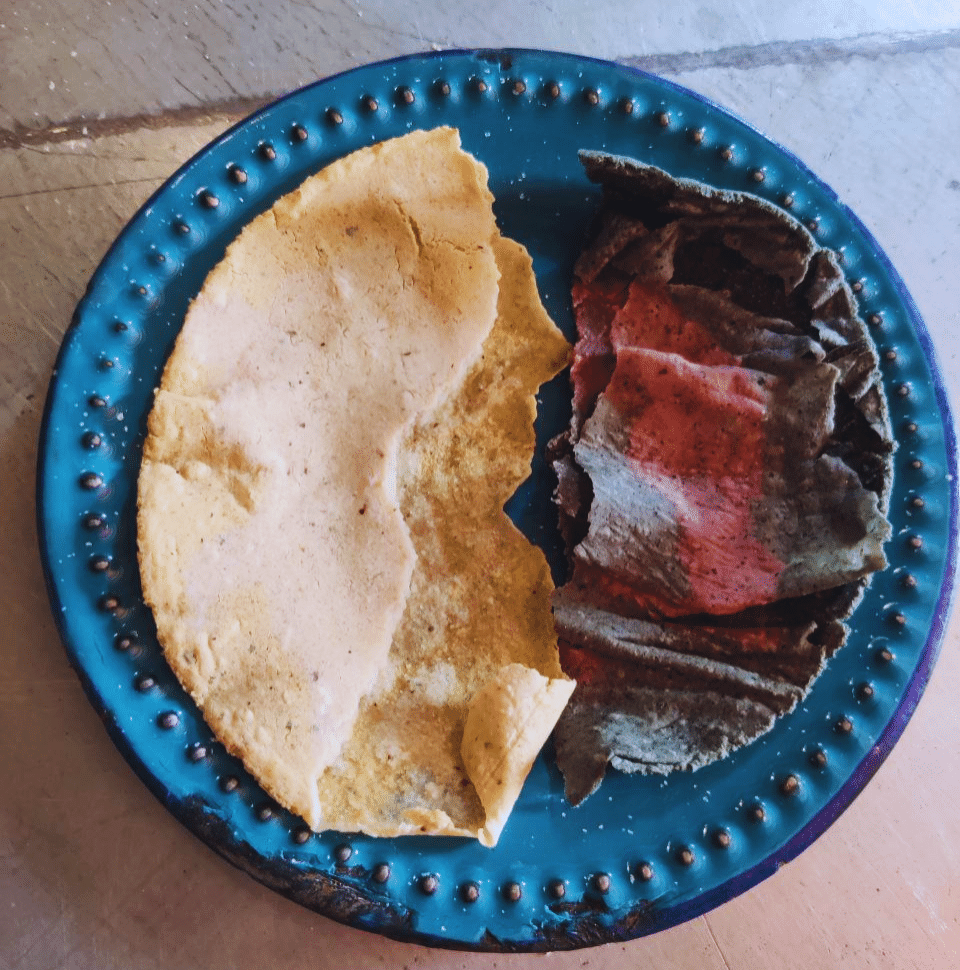

Blanca Mejía, a third-generation tortilla producer, explained that ”the big industry lets the tortilla soak for two hours, while we let it soak for 16 hours so that the grain opens up, absorbs the minerals from the lime and calcium, and enters into symbiosis with each other. It is like a marinade. Following these hours, the maize pericarp (coat of the corn) softens and can be crushed in the mills. The big industry removes the pericarp because, after two hours, it is hard. Then it washes and dries the corn and adds additives, binders, and chemicals to replace the benefits and goodness of the pericarp.”

”Academia, civil society, and other sectors did not agree with how the definition was left, but other groups, the big industry, did agree. That creates an imbalance,” said the anonymous source, who is close to the health sector.

In that imbalance, areas within the tortilla business, such as small corn producers and nixtamal mills, are left out of the NOM conversation. Santiago Muñoz, co-founder of Maizajo, a nixtamal mill and tortilla factory located in Mexico City that nixtamalizes in the traditional way, told Empower that ”Maseca comes and says, ’you buy the product, I’ll provide the machine,’ so, let’s say it’s a family of three, all three are dedicated to that activity. Then they bring them the flour, they add water, they stir, and that’s it.”

“The word ’nixtamalized’ leads consumers to believe that the product has the properties of nixtamalization, which can only be obtained if it is corn masa. Therefore, the use of the word ‘nixtamalized’ in products that use flour and do not acquire the same properties implies tricking consumers,” said the organization El Poder del Consumidor as part of the public comments open to all participants that Empower reviewed.

Although it is not possible to speak of industry interference in the NOM-187 process per se, since, by law, the private sector is invited to participate, an analysis of the comments issued by companies and associations representing industry, carried out by Empower, reveals the interests that this group fought for, although in the latest version of the NOM several of their proposals were not approved.

Regarding the definition of nixtamalization, the National Chamber of Industrialized Corn (CANAMI) and the CNA proposed allowing ”the use of other alkaline materials in the nixtamalization process, since calcium hydroxide (lime) is not the only one.” Their reason was that, with calcium salts, there is a more ”sustainable and ecological” process.

The “flourization” oligopoly

For decades, Maseca, part of the Gruma conglomerate, directed its advertising to communicate that corn flour had health benefits because it contains added vitamins and is ”tastier, whiter.”4Maseca TV commercial, YouTube, accessed 12 September 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=JMkUVNi4K-I.

In a TV commercial from the 1990s, a line of people can be seen where others arrive asking phrases such as ”do they sell energy here, is this where you buy calcium, is this the line for the healthiest stuff, and is this where they have folic acid” and others answering ”yes” to all the questions. The ad ends with a voice-over saying ”always look for tortillerías that make their tortillas with 100% natural Maseca corn flour, which, besides having calcium, contain added iron, zinc, and folic acid.”5Ibid.

This narrative, together with other strategies implemented by Gruma and Minsa, which researcher Gustavo Vargas Sánchez calls an oligopoly, has led to a ”flourization” of the tortilla market. Some of these strategies are the idealization of the industrialization of nixtamalized corn, demand creation, and becoming part of a market with rigid demand, such as the purchase of tortilla factories, so as to become an indispensable raw material, according to his study ”The corn flour market in Mexico. A macroeconomic interpretation.”6“El mercado de harina de maíz en México. Una interpretación macroeconómica,” Gustavo Vargas Sánchez, Elsevier, vol. 405, pages 4-29, July-August 2017, accessed 12 September 2022, www.elsevier.es/en-revista-economia-informa-114-articulo-el-mercado-harina-maiz-mexico—S0185084917300324.

For years, Gruma and Minsa also participated in the market without a NOM, until 2003, when the first version of the NOM that will now be replaced was drafted. However, on that occasion, there was not a large number of groups opposed to the industry’s interests. The list of those who participated in the creation of the norm included mostly government agencies and companies, including Minsa and Gruma.7“NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-187-SSA1/SCFI-2002, Productos y servicios. Masa, tortillas, tostadas y harinas preparadas para su elaboración y establecimientos donde se procesan. Especificaciones sanitarias. Información comercial. Métodos de prueba,” Diario Oficial de la Federación, 18 August 2003, https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=691995&fecha=18/08/2003#gsc.tab=0.

Gruma has held positions among the economic elite since its foundation in 1949. It was founded by Roberto González Barrera, who also started Grupo Financiero Banorte together with Carlos Hank González. The boards of both companies have been controlled by the González family. Gruma is currently managed by Juan Antonio González Moreno. Since 2016, workers at Mission Foods in the United States, a subsidiary of Gruma, have confronted the company for prohibiting them from being part of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW).8“USA: Pennsylvania Gruma/Mission Foods Workers Fighting Back,” IU, 28 April 2017, www.iuf.org/news/usa-pennsylvania-gruma-mission-foods-workers-fighting-back.

Between 2016-18, Gruma obtained public contracts with the Mexican government worth 667,677,283 pesos, according to Compranet, consulted through QuiénEsQuién.Wiki.

For its part, Grupo Minsa is part of Consorcio Grupo G, S.A. de C.V.,9“Somos parte de una gran,” DINA, tinyurl.com/36ac9535. owned by a family of brothers from Jalisco, Rafael, Arando, Guillermo, Alfonso, and Raymundo Gómez Flores, and their father, Alfonso Gómez Somellera. The other companies that comprise the Grupo are Consorcio Inmobiliario G, S.A. de C.V., Dina Camiones, S.A. de C.V., Almacenadora Mercader S.A. (ALMER), and Mercader Financial, S.A. SOFOM ER.10“Historia,” Dina, tinyurl.com/3y3hs7np. Minsa was founded in 1993, when it acquired five flour plants from Maíz Industrializado Conasupo, S.A. de C.V. (MICONSA),11“Convocatoria de venta y bases de licitación,” Diario Oficial de la Federación, tinyurl.com/55p6mjwf; “Grupo Minsa, S.A.B. de C.V.,” BVM, tinyurl.com/4k5r84e7. as well as the Minsa brand.12“Firma de inversiones de EU compra capital de Minsa,” Notimex, tinyurl.com/59a4mrvs.

The political and business scope of the Gómez family is more local to the state of Jalisco. For example, Omar Raymundo Gómez Flores, a director of Grupo Minsa since 2018, has been a senator for the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) (2000-03).13“Omar Raymundo Gómez Flores,” Sistema de Información Legislativa, tinyurl.com/yb45ad7a. In addition, he was coordinator of the advisory board of Jalisco a Futuro,14Jalisco a Futuro, www.jaliscoafuturo.mx/jalisco-a-futuro-2030. a project of the University of Guadalajara and the Economic and Social Council of the State of Jalisco for Development and Competitiveness (CEJSAL).

Moreover, Luis Antonio García Serrato, CEO of Grupo Minsa since 2017, was involved in allegations of monopolistic practices in the bean industry in 2006, in collusion with Manuel and Jorge Bribiesca Sahagún, the children of Marta María Sahagún Jiménez, wife of Vicente Fox Quesada, former president of Mexico (2000-06).15“Denuncian a hijos de Marta Sahagún,” El Siglo de Durango, tinyurl.com/5n827tr3. It is worth noting that Altagracia Gómez, president of the board of directors of Grupo Minsa since 2018, had a television program with Alfonso Gómez, head of the Secretary of Education of the State of Jalisco.16“Altagracia Gómez Sierra,” Instituto de la Mexicanidad, tinyurl.com/45mz6652.

Between 2016-21, Minsa obtained public contracts with the Mexican government worth 120,661,606 pesos, according to Compranet, consulted through QuiénEsQuién.Wiki.

Both Gruma and Minsa are members of CANAMI and CNA, and are participants in the NOM process. González Barrera, owner of Gruma, is also a member of the Mexican Business Council and CAINTRA.

The CNA, led by by Luis Fernando Haro Encinas and chaired by Juan Cortina Gallardo since 2010, also a director of Grupo Azucarero México, S.A. de C.V., obtained subsidies from the Mexican government, between 2009-18, worth 48,699,831 pesos for activities such as “support for forums, workshops and other training events”17“Buscador de OSC”, Comisión de Fomento de las Actividades de las Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil, Gobierno de México, consultado en septiembre 2022, www.sii.gob.mx/portal/?cluni=&nombre=CONSEJO+NACIONAL+AGROPECUARIO&acronimo=&rfc=&status_osc=&status_sancion=&figura_juridica=&estado=&municipio=&asentamiento=&cp=&rep_nombre=&rep_apaterno=&rep_amaterno=&num_notaria=&objeto_social=&red=&advanced=.. The largest amount it obtained was in 2016, when the SHCP granted 10,500,300 pesos for the CNA to carry out forums, workshops, and other training events under the National Financier of Agricultural, Rural, Forestry and Fisheries Development’s support program (FND) to access credit and promote economic and financial integration for rural development.18“Consejo Nacional Agropecuario S.A. RFC CNA840530V76. CLUNI CNA8405300901C. Oficina Registral: CDMX. No. de Escritura 74,138. Fecha 29/05/1984,” Sistema de Información del Registro Federal delas OSC (RFOSC), 2022, Op.Cit. CNA also opposed the ban on glyphosate in Mexico.19“Carta a Juez Octavo y Secretaria de Juzgado Octavo, en donde exigimos NO dar suspensión definitiva al CNA,” CDH Vitoria, Op.Cit.

Minsa referred Empower to CANAMI to discuss the NOM and said it was not allowed to answer questions about its industrial processes due to trade secrecy reasons. CANAMI and Gruma responded that they could not give interviews about the NOM because they had signed a confidentiality agreement with the authorities in charge of the process.

Corn masa improvements are a detriment to public health

The definition of nixtamalization in the NOM-187 does not differentiate between artisanal and industrial processes, which will be reflected in the denomination, nor between the additives used and permitted for corn processing, according to Gabriela Guzmán, a lawyer in El Poder del Consumidor’s legal department, as explained to Empower.

The draft NOM-187,20“PROYECTO de Norma Oficial Mexicana PROY-NOM-187-SSA1/SE-2021, Productos de maíz y trigo-Denominaciones-Masa y productos derivados de masa-Especificaciones sanitarias-Información comercial y sanitaria-Métodos de prueba. (Cancelará a la Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-187-SSA1/SCFI-2002, Productos y servicios. Masa, tortillas, tostadas y harinas preparadas para su elaboración y establecimientos donde se procesan. Especificaciones sanitarias. Información comercial. Métodos de prueba, publicada 18 agosto 2003),” Diario Oficial de la Federación, 15 February 2022, www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5642778&fecha=15/02/2022#gsc.tab=0. which has already been published in the Official Journal of the Federation, defines ”Combined Additives” as the ”Mixture of two or more additives with different technological functions, which must guarantee that the additives with an Acceptable Daily Intake, according to the suggested use by the manufacturer, are used at the permitted levels.”

CANAMI, CNA, Nestlé, Bimbo, Gremab, and Investigación Técnica Avanzada (a Gruma subsidiary) requested the elimination of the numeral defining combined additives, according to the list of comments reviewed by Empower. If approved, this could mean even less control over the use and sale of these types of additives by the Federal Commission for Protection against Sanitary Risks (Cofepris). In fact, in the version of the norm that has not yet been approved or published, the number and definition of combined additives no longer appear.

The problem is that some of these combined additives are those known as ”corn masa improvements and tortilla improvements, which are currently not properly labeled. (…) It is very important to know [the specific content of each additive] because the level of exposure of Mexicans, when consuming a large amount of tortilla, is considerable, in addition to the fact that tostadas are associated with extreme heating of the preservatives and other additives included in such mixtures. The exposure faced by Mexicans when consuming tortillas with the unknown content of such additives is unknown,” according to the public observations made by the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

”Well, they arrive in a little car and give you their catalog. I had their bottles once, I said, ‘Oh, let’s see,’ just out of curiosity. These are bottles without labels. It just says ‘improvement.’ They tell you: ‘I bring corn improvements.’ There is a thing they put in the masa that expands and gives you more yield. We always tell them not to even come,” said Santiago Muñoz, from Maizajo, which does not use additives on the corn it buys directly from small producers.

However, the demand for corn products and a lack of knowledge has led some corn mills to put additives in their masa. Muñoz witnessed this when he went to nixtamalize his corn before he had his own mill. ”They would pour bleach in a little bottle, a transparent liquid would come out, and the masa would come out white. To me, when the masa comes out white, it’s already spoiled.”

The only reference to a combined additive in the May 28, 2022 version of the norm is in a table describing that, as part of the minimum information in the logs or records, it is necessary to “indicate the specific name of each of the additives present in the mixture, brand, and supplier data.”

Beyond the fact that the names of the additives in the mixtures are specified, what’s worrisome for Guzmán of El Poder del Consumidor is that ”the consumer does not know the true nature or the risks and effects of the mixtures on health. Possibly the companies know these effects, but we are not certain that the authority is aware of them.”

Informational letter about additives written by manufacturers

Food additives are defined as ”Any substance that is not normally consumed as a food, nor used as a basic ingredient in food, whether or not it has nutritional value, and whose addition to the product for technological purposes at the stages of production, processing, preparation, treatment, packing, transport, or storage results or may reasonably be expected to result (directly or indirectly) by itself, or by-products thereof, in a component of the product or an element affecting its characteristics (including organoleptic characteristics). This definition does not include ‘pollutants’ or substances added to the product to maintain or improve nutritional qualities.”

In this area, the industry was against providing detailed information about the additives used in corn masa. CANAMI and Gruma’s subsidiaries, Investigación Técnica Avanzada and Mission Foods México, proposed, in order to protect their trade secrets, to ”issue a letter of compliance with the Additives Agreement,” which the CNA was commissioned to write.

The ”informational letter about additives in products regulated by NOM-187-SSA1/SE-2021,” as found in the Working Group’s blog, defines what additives are contained in the product sold. From the time that the NOM is approved, if it is approved in terms identical to the latest version, it will be drafted by the same additive manufacturers and corn flour suppliers, such as Gruma and Minsa, and delivered to tortillería factories and nixtamal mills, stating that their product complies with the limits indicated in the Additives Agreement.

In other words, the industry that seeks to regulate NOM-187 will be responsible for expressing that it complies with the norm, which does not specify how Cofepris will monitor compliance with the Additives Agreement.

Between 2012 and 2022, Cofepris conducted only seven compliance and verification visits under the Additives Agreement for NOM-187 ofcompanies and individuals about the use of authorized additives for nixtamalized corn products, according to an information request submitted for this article. The seven verifications were conducted in 2021 in light of the resumption of business operations amidst the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Additives Agreement referred to in the NOM ”also has inconsistencies because, unlike a law or a norm that has a periodicity to be reviewed, this one does not. A person can propose a change and it can be done at any time,” said a source who participates in the process and preferred anonymity.

An informative poster in tortillerías

When NOM-187 is approved, tortillería factories will be forced to display a poster visible to the consumer with the list of ingredients, additives, and recommendations for consumption of their product.

”Who is going to check for compliance?,” asked Santiago Muñoz, who acknowledges the good intentions of requiring such a poster and assures that his establishment, Maizajo, will comply.

Whether or not the industry informs consumers, the definition of nixtamalization becomes key. Since industrial nixtamalization causes corn to lose nutrients, nixtamalized corn flour must have folic acid, zinc, and iron added to it and be restored with vitamins B1, B2, and niacin. And this is informed on the packaging.

During the NOM process, civil society organizations and health institutes fought for this information to be removed from the denomination, since traditionally nixtamalized corn does not require additives since it does not lose its properties, as is the case during the industrial process.

According to one of the sources involved in the development of the norm, ”people might think that corn flour is more nutritious because they are adding all that. But, in the end, the population does not know that it is a legal obligation and it puts nixtamalized corn products at a disadvantage.”

Regarding this specific item, there was no opportunity for discussion, since it was not initially considered as a point for discussion. ”Cofepris skipped its own processes because it had said that only issues that came out of the comments to the public consultation would be resolved, and this did not come out of that,” said the source.

For its part, Gruma sent a comment in which it justified informing the public about nutritional additions as a regulatory and public health issue.

“Dough mixtures can be (1) corn masa to which flour is added, or (2) flour masa to which corn masa is added. It is important that vitamins and minerals are added and restored to the masa and nixtamalized corn flour according to the normative reference. Dough should not be exempted from complying with an important public health policy,” reads the document to which Empower had access.

Changes in Economy, the process on pause

The revision of NOM-187, initiated in 2019, should have been completed by April 2022; however, it is currently on pause following the departure of Alfonso Guati Rojo as general director of Norms at the Secretary of the Economy (SE) on May 31 and the arrival of Eduardo Montemayor Treviño, originally from Monterrey, to replace him.

Treviño, who is 32 years old, was general director of Constitutional and Legal Procedures within the SE during seven months before being appointed to his new position. Prior to the SE, he worked for private law firms. In 2013, he became a partner at Mohav Industrial Group, a producer and distributor of food supplements, medicines, and health supplies. He is also listed as a partner of the law firm My Dear Lawyers, since 2018, and of Frumarket SCL, since 2019, a producer and marketer of agricultural products.

In his patrimonial declarations as a public official, Montemayor only declared his company My Dear Lawyers. According to the information contained in the Public Registry of Property and Digital Commerce (Siger), there have been no changes in the shares or corporate structure of his companies. On the Compranet platform, consulted through QuiénEsQuién.Wiki, none of his firms appear to have received government contracts.

Montemayor Treviño actively collaborated with Tatiana Clouthier, current head of the SE, during 2012 in the “Antichapulinazo” collective, which Montemayor represented in a legal process against Fernando Larrazabal Betrón, PAN mayor of Monterrey, for requesting a leave of absence from his office to campaign for a federal congressional seat.21His participation was on behalf of the civic organizations that comprise the “Antichapulinazo” Collective. “Doble decisión judicial en caso Larrazabal: tribunal le niega licencia; un juez la avala,” María Alejandra Arroyo, tinyurl.com/2p99ucce.

Sources involved in the review of NOM-187 assured that, in interviews conducted during August and September 2022, Montemayor Treviño had not approached them nor had they been called by the SE or Cofepris to resume the process. Neither of the agencies was available for an interview before this article went to publication.

As of today, September 29, 2022, which commemorates National Corn Day, there is no date for the publication of the most important regulation for the production and marketing of products derived from this grain, a historical pillar for the national diet and basic input for more than 110,000 tortilla factories in Mexico, according to the National Statistical Directory of Economic Units (DENUE) 2019.22“En México ya hay más de 110,000 tortillerías,” Economía Hoy, 21 February 2020, www.economiahoy.mx/empresas-eAm-mexico/noticias/10372392/02/20/En-Mexico-ya-hay-mas-de-110000-tortillerias.html.

1 According to National Geographic, nixtamalization is “ a process in which dried maize is soaked, then cooked in an alkaline solution that softens corn and renders it more digestible.”, Erin Blakemore, “Who were the Maya? Decoding the ancient civilization’s secrets”, National Geographic, 7 September 2022 www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/who-were-the-maya.

2 “Maquinaria,” Gruma, accessed 11 September 2022, www.gruma.com/es/innovacion/tecnologia/maquinaria.aspx.

3 “Maseca, conserva el proceso tradicional de la nixtamalización: especialistas,” Dinero en Imagen, 21 January 2020, www.dineroenimagen.com/empresas/maseca-conserva-el-proceso-tradicional-de-la-nixtamalizacion-especialistas/118952.

4 Maseca TV commercial, YouTube, accessed 12 September 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=JMkUVNi4K-I.

5 Ibid.

6 “El mercado de harina de maíz en México. Una interpretación macroeconómica,” Gustavo Vargas Sánchez, Elsevier, vol. 405, pages 4-29, July-August 2017, accessed 12 September 2022, www.elsevier.es/en-revista-economia-informa-114-articulo-el-mercado-harina-maiz-mexico—S0185084917300324.

7 “NORMA Oficial Mexicana NOM-187-SSA1/SCFI-2002, Productos y servicios. Masa, tortillas, tostadas y harinas preparadas para su elaboración y establecimientos donde se procesan. Especificaciones sanitarias. Información comercial. Métodos de prueba,” Diario Oficial de la Federación, 18 August 2003, https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=691995&fecha=18/08/2003#gsc.tab=0.

8 “USA: Pennsylvania Gruma/Mission Foods Workers Fighting Back,” IU, 28 April 2017, www.iuf.org/news/usa-pennsylvania-gruma-mission-foods-workers-fighting-back.

9 “Somos parte de una gran,” DINA, tinyurl.com/36ac9535.

10 “Historia,” Dina, tinyurl.com/3y3hs7np.

11 “Convocatoria de venta y bases de licitación,” Diario Oficial de la Federación, tinyurl.com/55p6mjwf; “Grupo Minsa, S.A.B. de C.V.,” BVM, tinyurl.com/4k5r84e7.

12 “Firma de inversiones de EU compra capital de Minsa,” Notimex, tinyurl.com/59a4mrvs.

13 “Omar Raymundo Gómez Flores,” Sistema de Información Legislativa, tinyurl.com/yb45ad7a.

14 Jalisco a Futuro, www.jaliscoafuturo.mx/jalisco-a-futuro-2030.

15 “Denuncian a hijos de Marta Sahagún,” El Siglo de Durango, tinyurl.com/5n827tr3.

16 “Altagracia Gómez Sierra,” Instituto de la Mexicanidad, tinyurl.com/45mz6652.

17 “Buscador de OSC”, Comisión de Fomento de las Actividades de las Organizaciones de la Sociedad Civil, Gobierno de México, consultado en septiembre 2022, www.sii.gob.mx/portal/?cluni=&nombre=CONSEJO+NACIONAL+AGROPECUARIO&acronimo=&rfc=&status_osc=&status_sancion=&figura_juridica=&estado=&municipio=&asentamiento=&cp=&rep_nombre=&rep_apaterno=&rep_amaterno=&num_notaria=&objeto_social=&red=&advanced=.

18 “Consejo Nacional Agropecuario S.A. RFC CNA840530V76. CLUNI CNA8405300901C. Oficina Registral: CDMX. No. de Escritura 74,138. Fecha 29/05/1984,” Sistema de Información del Registro Federal delas OSC (RFOSC), 2022, Op.Cit.

19 “Carta a Juez Octavo y Secretaria de Juzgado Octavo, en donde exigimos NO dar suspensión definitiva al CNA,” CDH Vitoria, Op.Cit.

20 “PROYECTO de Norma Oficial Mexicana PROY-NOM-187-SSA1/SE-2021, Productos de maíz y trigo-Denominaciones-Masa y productos derivados de masa-Especificaciones sanitarias-Información comercial y sanitaria-Métodos de prueba. (Cancelará a la Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-187-SSA1/SCFI-2002, Productos y servicios. Masa, tortillas, tostadas y harinas preparadas para su elaboración y establecimientos donde se procesan. Especificaciones sanitarias. Información comercial. Métodos de prueba, publicada 18 agosto 2003),” Diario Oficial de la Federación, 15 February 2022, www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5642778&fecha=15/02/2022#gsc.tab=0.

21 His participation was on behalf of the civic organizations that comprise the “Antichapulinazo” Collective. “Doble decisión judicial en caso Larrazabal: tribunal le niega licencia; un juez la avala,” María Alejandra Arroyo, tinyurl.com/2p99ucce.

22 “En México ya hay más de 110,000 tortillerías,” Economía Hoy, 21 February 2020, www.economiahoy.mx/empresas-eAm-mexico/noticias/10372392/02/20/En-Mexico-ya-hay-mas-de-110000-tortillerias.html.