Leidos builds U.S. digital border wall and supplies the Mexican government

23 de February de 2023

Translated from Spanish

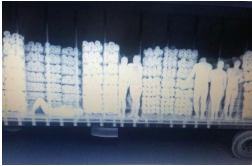

A new kind of anti-undocumented immigrant wall is being erected along the U.S.-Mexico border. It is a digital border wall built with technologies ranging from the use of artificial intelligence and biometric data for surveillance to “non-intrusive” technologies, such as the use of X-rays and gamma rays to inspect cargo vehicles. After a truck overcrowded with 67 immigrants, 53 of whom died, went undetected crossing the border near San Antonio, Texas, two U.S. senators proposed an initiative to strengthen the use of scanners and President Joseph Biden spoke of the same need in a summit earlier this year with the presidents of Mexico and Canada. The largest contractor for these inspection systems is the company Leidos, whose contract with U.S. Customs and Border Protection ends in 2032. Additionally, Empower found that Leidos has had public contracts in Mexico worth more than 1.075 billion Mexican pesos. The effectiveness of these technologies for controlling drug smuggling and human trafficking has been called into question when it comes to prioritizing the human rights of immigrants.

By Elizabeth Rosales

The use of radiation to detect and prevent drug and human trafficking is a priority task for the United States as part of its efforts to strengthen the digital border wall, comprised of technologies such as drones, motion sensors, and autonomous surveillance towers that seek to prevent undocumented people from crossing the border.

On January 10, 2023, at the North American Leaders’ Summit (NALS), President Biden boasted that his administration deploys trucks that allow it to expedite the cargo screening process using X-ray inspection and assured that it is necessary to increase technological capabilities along the border with Mexico.

“Both to intercept illegal drugs and other contraband, as well as people being smuggled across the border,” Biden said during the Q&A section of the Summit.

To equip and maintain these X-ray and gamma scanners, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), through the Department of Homeland Security, awarded a contract ending in 2032 to the technology firm Leidos, Inc., according to CBP’s FY2023 budget overview.1“CBP – Budget Overview,” DHS, 2023, www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/U.S.%20Customs%20and%20Border%20Protection_Remediated.pdf.

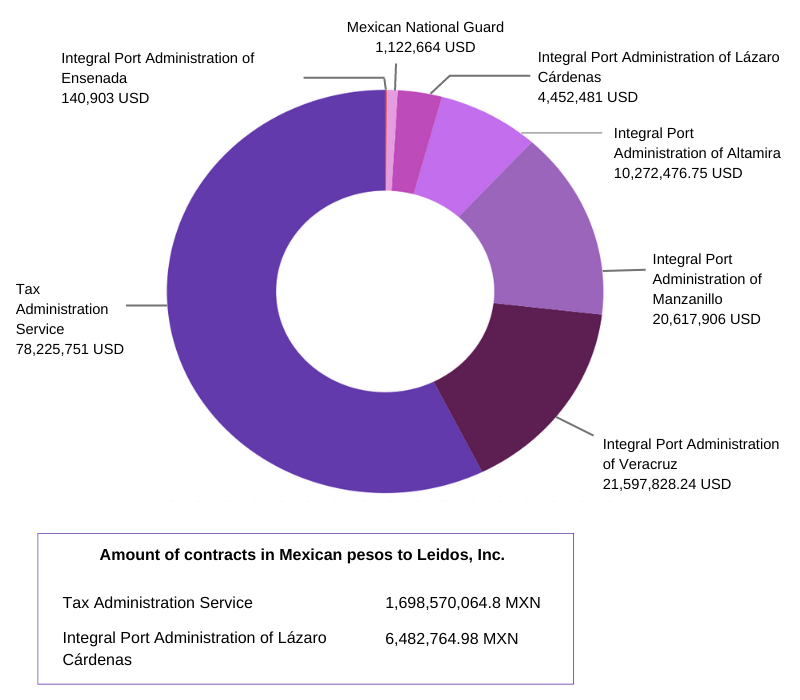

It is worth mentioning that Leidos is also a supplier to the Mexican government, particularly to the National Guard, the Tax Administration Service (SAT), and five parastate companies of the Integral Port Administration (API), according to information published on Compranet.

There is no public data about the number of arrests made in Mexico or in the U.S. using these technologies, but the digital border wall generates a discussion about its potential to violate human rights on issues ranging from digital privacy to physical integrity. This includes, for example, the use of biometric data for mass surveillance or the implementation of inspection machines that emit radiation capable of damaging DNA and causing cancer, according to the U.S. National Cancer Institute.2“Radiation”, U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), 7 March 2019, www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation.

“One of the things that happens is that there is a lot of opacity about what technology is being experimented with. We need to understand what public institutions are buying what technologies, for what purposes, and what kind of companies are providing them,” said Mayeli Sánchez, a researcher at Técnicas Rudas, an organization focused on social movements and human rights advocacy, in an interview with Empower.

Empower requested comments by e-mail from CBP and Mexican agencies using the same technology regarding the impact of these radiations and how they prevent these technologies from violating human rights; however, they did not respond by the requested deadline.

Between October 2020 and January 2023, immigrant detention along the U.S.-Mexico border tightened and increased, according to CBP data. A total of 5,438,967 undocumented individuals were apprehended at the U.S.’s southern border. According to CBP, 2022 was the year with the highest number of apprehensions during that period, with 2,378,944 cases,3“Nationwide encounters,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2020-23, www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/nationwide-encounters. equivalent to an increase of 419.32% compared to 2020.

On the other hand, in 2020, CBP intercepted 320,689 kilograms of drugs such as marijuana, methamphetamine, cocaine, and fentanyl, to name a few. In 2021, 40.72% of illicit drugs seized by CBP were detected through the use of non-intrusive inspection systems at border checkpoints or ports of entry.4“Peters and Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Improve Screening of Vehicles and Cargo at Ports of Entry,” U.S. Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, July 2022, www.hsgac.senate.gov/media/majority-media/peters-and-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-improve-screening-of-vehicles-and-cargo-at-ports-of-entry.

“Technologies deployed to our Nation’s land, sea, and air ports of entry include large-scale X-ray and gamma-ray imaging systems, as well as a variety of portable and handheld technologies,” explains a CBP document.5“Non-intrusive Inspection (NII) Technology,” CBP, May 2013, www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/nii_factsheet_2.pdf.

According to Sánchez, governments try to justify the use of various technologies by appealing to crime prevention when there is no guarantee that this works, when their actual use is to keep society under control.

Leidos is watching

Between 1994 and 2022, Leidos, Inc., one of CBP’s so-called “non-intrusive” technology providers, received more than 108 billion USD6In the U.S., public procurements are registered with a total obligated amount, but there is also a potential total amount that may be exercised if justified. See: “Element: Amount of Award, Federal Action Obligation, Non-Federal Funding Amount, Current Total Value of Award, and Potential Total Value of Award,” Federal Spending Transparency, August 2015, https://fedspendingtransparency.github.io/whitepapers/amount/#:~:text=and%20exercised%20options.-,Potential%20Total%20Value%20of%20Award,and%20all%20options%20are%20exercised; and “Contratos EE.UU – Leidos,” USA Spending, 1994-2022, https://share.mayfirst.org/s/BrRZtQjMxmLHQBt. as a “total obligated amount.”7“Element: Amount of Award, Federal Action Obligation, Non-Federal Funding Amount, Current Total Value of Award, and Potential Total Value of Award,” Federal Spending Transparency, August 2015, https://fedspendingtransparency.github.io/whitepapers/amount/#:~:text=and%20exercise.

Empower found that 27 contracts with a total value of 249,949,706.511 USD8“Contratos EE.UU – Leidos,” USA Spending, 1994-2022, https://share.mayfirst.org/s/BrRZtQjMxmLHQBt. were to provide technology to the Department of Homeland Security, particularly to CBP and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the agency responsible for deportations in that country. Among the contracts analyzed were X-ray and gamma-ray inspection systems.

According to CBP’s FY2023 budget overview, Leidos is its main supplier with the largest contract to continue the non-intrusive inspection program through 2032.9“CBP – Budget Overview,” DHS, 2023, www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/U.S.%20Customs%20and%20Border%20Protection_Remediated.pdf.

Its parent company, Leidos Holdings, Inc. (NYSE:LDOS), is headquartered in the state of Virginia, just outside Washington, D.C., and is a public company listed on the New York Stock Exchange.10“Leidos, Form 10-Q,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 30 September 2022, https://s22.q4cdn.com/107245822/files/doc_financials/2022/q3/cedbb90d-6b5f-4f4f-8b74-5cd0629a0e1c.pdf.

The company’s major shareholders are mutual fund managers, such as Vanguard Group, Inc. (11%), BlackRock Inc. (9.84%), JP Morgan Asset Management (4.10%), State Street Global Advisors Inc. (4.06%), and Wellington Management Group, LLP (3.79%).

Knowing what technologies are used to detect and identify immigrants at the border and/or within countries should be a matter of public interest due to the effect on the fundamental rights of a particularly vulnerable group of people, such as immigrants. The violation of their rights should always be considered extremely serious and important, according to Franco Giandana, lawyer and analyst at Access Now, an organization focused on the legal instruments and technologies that enable the cross-border exchange of sensitive data of immigrants between Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and the U.S.

Leidos in Mexico

Mexican institutions also have technology that allows them to perform the same type of detections in ports of entry, according to public contracts to which Empower had access and where Leidos provided installation, relocation, preventive services, and corrective maintenance of gamma and X-ray equipment to the National Guard, the SAT, and five parastate companies of the API, located in the ports of Altamira, Tamaulipas; Ensenada, Baja California; Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán; Manzanillo, Colima; and Veracruz, Veracruz.

Leidos has had 36 contracts with those agencies between 2014 and 2021 worth a total of 136,430,009.99 USD, in addition to 1,705,052,829.78 Mexican pesos for the installation, relocation, preventive services, and corrective maintenance of gamma and X-ray equipment, according to Compranet data.

“We are such a good market that if you want to show that your product works, just come to Mexico and we will test it for you,” said Mayeli Sánchez of Técnicas Rudas, after recalling that Mexico is one of the countries that buys the most surveillance technologies.

According to José María Ramos, researcher at the Department of Public Administration Studies at the Colegio de la Frontera Norte (Colef), these inspection systems do not imply the existence in Mexico of a comprehensive agenda to address risks and threats in cases of terrorism, drug trafficking, and cyber risks. That is why “I see a great contradiction of the Mexican State that is not proposing an agenda in this regard,” said Ramos.

In order to operate in Mexico, Leidos, Inc. registered as a foreign corporation in Mexico City in 2021, with the corporate purpose of “engaging in general trade and commerce as permitted by law in Mexico, including the processing, purchase, sale, lease, marketing, import, export, storage, packaging, distribution, delivery, installation, and promotion of products, including non-intrusive security and inspection devices, such as inspection, multi-view, and X-ray equipment or gamma-ray equipment and systems, as well as related products or materials,” according to the corporate records consulted by Empower.

The person who requested the notarization of said minutes in Mexico is Jorge Manuel Ogarrio Kalb, an attorney specializing in corporate law11“Los Consejos Directivos y su Adaptación a la Tecnología durante la Pandemia,” Foro Jurídico, 1 October 2021, forojuridico.mx/lo-consejos-directivos-y-su-adaptacion-a-la-tecnologia-durante-la-pandemia. and a Mexican national by birth. After being contacted by e-mail, Ogarrio said that he had forwarded Empower’s request for comment to Leidos, Inc. and assured that he is not a shareholder and has no further information about the company.

In the Integrated System for the Management of the Property Registry (SIGER, in Spanish), the company’s articles of incorporation are not available. Therefore, Leidos’ shareholders are not publicly listed and only its representatives in Mexico are named: Jorge Ogarrio Kalb, Jesús Cutbero Pérez Cisneros, and Rodolfo Cortés González. Empower also attempted to establish contact with the latter two through LinkedIn, but neither of them responded.

But this is not its only link to Mexico. One of Leidos’s main suppliers is the Mexican company Intercambio Comercial, S.A. de C.V., based in Naucalpan de Juárez, State of Mexico, according to export and import records obtained by Empower.

Intercambio Comercial has purchased components, such as electrical switches, modular circuit boards, closed circuit cameras, photoelectric sensors and computers, among other products, which it first imported into Mexico, mainly from China, and then exported to the U.S. for Leidos, Inc. Empower found 28 shipments of Chinese origin that passed through Mexico to eventually reach Leidos through Intercambio Comercial, S.A. de C.V.12“Base de datos de envíos – Intercambio Comercial a Leidos, Inc.,” Panjiva, 2018-22, https://share.mayfirst.org/s/dAXYDFPKKWEbRx6.

It is worth mentioning that the United States has restrictions in place to prevent the importation of products manufactured with forced labor and has maintained a public registry of banned companies and regions since 1991, where China has been one of its main concerns.13“Withhold Release Orders and Findings List,” CBP, 1991-23, www.cbp.gov/trade/forced-labor/withhold-release-orders-and-findings.

The importer Intercambio Comercial, S.A. de C.V. is legally represented by the businessman Alain Elie Gugenheim Dalsace, according to corporate records consulted by Empower.

Empower attempted to contact both the company and its representative by phone and e-mail for this article. However, neither could be reached.14The company’s e-mail address is no longer available and no one answers the phone number that is linked to the company. Google searches show that the company is “permanently closed,” although its status with the Public Registry of Commerce remains open.

Technology that detects immigrants but does not save them

CBP’s Non-Intrusive Inspection Systems Program allows for the screening of cargo and conveyances through the use of X-ray and gamma-ray imaging systems.15“DHS/CBP/PIA-017 Non-Intrusive Inspection Systems Program,” CBP, June 2021, www.dhs.gov/publication/non-intrusive-inspection-systems-program. Non-intrusive inspection generally allows for the examination of cargo transport, such as sea containers, commercial trucks, and rail cars, as well as privately-owned vehicles without physically opening or unloading them, according to CBP.16“Non-intrusive Inspection (NII) Technology,” CBP, May 2013, www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/nii_factsheet_2.pdf.

“Customs and Border Protection uses Non-Intrusive Inspection technologies to help detect and prevent contraband, including drugs, unreported currency, guns, ammunition, and other illegal merchandise, as well as inadmissible persons, from being smuggled, trafficked, or otherwise imported contrary to law, into the United States.”17“DHS/CBP/PIA-017 Non-Intrusive Inspection Systems Program,” CBP, June 2021, www.dhs.gov/publication/non-intrusive-inspection-systems-program.

In 2013, CBP claimed to screen, using non-intrusive inspection technology, 100% of the cars and commercial vehicles at its ports of entry, as well as 99% of cargo arriving in the U.S. by sea.18“Non-intrusive Inspection (NII) Technology,” CBP, May 2013, www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/nii_factsheet_2.pdf. However, in June 2022, a truck containing more than 50 dead or dying immigrants made it to San Antonio, Texas, after passing through a federal immigration checkpoint without being inspected.19“Truck Carrying Dead Migrants Passed Through U.S. Checkpoint,” The New York Times, 29 June 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/06/29/us/texas-migrants-deaths-truck.html.

Upon that discovery, a CBP official told The New York Times that “truck traffic is too voluminous” and it has been difficult for them to control all the vehicles crossing the border.

“The secondary inspection areas are not very large. We are talking that if, per day, about 500 carriers cross through Tijuana, those that pass to secondary inspection are, I would say, less than two or three percent because the U.S. authorities do not have the capacity to do so, which also happens with other vehicles,” observed Ramos, Colef professor.

One month after the trailer was discovered in San Antonio, Senators Gary Peters and John Cornyn introduced a bill proposing to increase the use of non-intrusive inspection systems and urge the CBP to “scan at least 40% of passenger vehicles and at least 90% of commercial vehicles entering the United States by land by the end of fiscal year 2024.”20“Peters and Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Improve Screening of Vehicles and Cargo at Ports of Entry,” U.S. Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, July 2022, www.hsgac.senate.gov/media/majority-media/peters-and-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-improve-screening-of-vehicles-and-cargo-at-ports-of-entry.

Each year, goods with a cumulative value of more than 30 billion USD circulate between Texas and Mexico alone, according to Senator Cornyn.21“Peters and Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Improve Screening of Vehicles and Cargo at Ports of Entry,” U.S. Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, July 2022, www.hsgac.senate.gov/media/majority-media/peters-and-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-improve-screening-of-vehicles-and-cargo-at-ports-of-entry.

Human rights violations and the “other” wall

In reality, the U.S. government’s “prevention” work begins thousands of miles south, on the border of Mexico and Central America.

In 2022 alone, 47.57% of undocumented immigrants in Mexico came from Central America, according to the Government of Mexico’s Unit of Migration Policy, Registration, and Identity.22“Boletines estadísticos,” Gobierno de México, 2022, www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/CuadrosBOLETIN?Anual=2022&Secc=3.

Over the course of the current federal administration, the United States has provided millions of dollars to Central America to promote jobs creation in those countries, investment, and food security, among other tactics aimed at decreasing the migration of people from those countries to the U.S.

In addition, the U.S. has agreements with Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras to share their citizens’ biometric data with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, according to research done by Empower’s Technology and Human Rights area.23Empower submitted freedom of information requests to Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Mexico to confirm the existence of agreements that facilitate the exchange of biometric data. Non-governmental organizations such as Access Now and R3D, which advocate for the digital rights of immigrants, have also denounced this recently. See: “Alerta migrante: tus datos biométricos pueden estar siendo intercambiados con EEUU,” Access Now, 10 January 2023, www.accessnow.org/acuerdos-datos-biometricos-migrantes.

This allows them to learn the identity of an undocumented person, though it is a practice that generates concern among specialists.

According to Access Now’s Giandana, there is a chance that the data shared with the U.S. may be disproportionate and have potential negative effects on immigrants.

“Not only can the right to privacy be affected, but also the protection of their personal data, the exercise of freedom of movement, of association, and the presumption of innocence that should prevail in a state of law,” he said.

Empower requested comments from Leidos, Inc. in the United States and its legal representatives in Mexico, as well as from Intercambio Comercial, S.A. de C.V., the Mexican National Guard, SAT, and the Secretariat of Infrastructure, Communications and Transportation as the tendering body for API’s concessions, but none responded by the requested deadline.

In Sanchez’s opinion, the security of a country cannot be linked to a system of surveillance and social control, even if the institutions try to sell us the idea that we need to use these technologies for preventive and even punitive purposes to find “criminals.”

“These technologies remind us once again that the optimism placed in digitized solutions often requires public scrutiny and audit, in relation to the alleged benefits they offer,” agreed Giandana.

Paradoxically, countries such as the U.S. and Mexico praise mass inspection and surveillance as a tool to promote citizen security, while those same technologies continue failing to protect the lives of immigrants, as happened with the people who died trying to cross by truck into San Antonio, Texas.

1 “CBP – Budget Overview,” DHS, 2023, www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/U.S.%20Customs%20and%20Border%20Protection_Remediated.pdf.

2 “Radiation”, U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), 7 March 2019, www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/radiation.

3 “Nationwide encounters,” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2020-23, www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/nationwide-encounters.

4 “Peters and Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Improve Screening of Vehicles and Cargo at Ports of Entry,” U.S. Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, July 2022, www.hsgac.senate.gov/media/majority-media/peters-and-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-improve-screening-of-vehicles-and-cargo-at-ports-of-entry.

5 “Non-intrusive Inspection (NII) Technology,” CBP, May 2013, www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/nii_factsheet_2.pdf.

6 In the U.S., public procurements are registered with a total obligated amount, but there is also a potential total amount that may be exercised if justified. See: “Element: Amount of Award, Federal Action Obligation, Non-Federal Funding Amount, Current Total Value of Award, and Potential Total Value of Award,” Federal Spending Transparency, August 2015, https://fedspendingtransparency.github.io/whitepapers/amount/#:~:text=and%20exercised%20options.-,Potential%20Total%20Value%20of%20Award,and%20all%20options%20are%20exercised; and “Contratos EE.UU – Leidos,” USA Spending, 1994-2022, https://share.mayfirst.org/s/BrRZtQjMxmLHQBt.

7 “Element: Amount of Award, Federal Action Obligation, Non-Federal Funding Amount, Current Total Value of Award, and Potential Total Value of Award,” Federal Spending Transparency, August 2015, https://fedspendingtransparency.github.io/whitepapers/amount/#:~:text=and%20exercise.

8 “Contratos EE.UU – Leidos,” USA Spending, 1994-2022, https://share.mayfirst.org/s/BrRZtQjMxmLHQBt.

9 “CBP – Budget Overview,” DHS, 2023, www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/2022-03/U.S.%20Customs%20and%20Border%20Protection_Remediated.pdf.

10 “Leidos, Form 10-Q,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 30 September 2022, https://s22.q4cdn.com/107245822/files/doc_financials/2022/q3/cedbb90d-6b5f-4f4f-8b74-5cd0629a0e1c.pdf.

11 “Los Consejos Directivos y su Adaptación a la Tecnología durante la Pandemia,” Foro Jurídico, 1 October 2021, forojuridico.mx/lo-consejos-directivos-y-su-adaptacion-a-la-tecnologia-durante-la-pandemia.

12 “Base de datos de envíos – Intercambio Comercial a Leidos, Inc.,” Panjiva, 2018-22, https://share.mayfirst.org/s/dAXYDFPKKWEbRx6.

13 “Withhold Release Orders and Findings List,” CBP, 1991-23, www.cbp.gov/trade/forced-labor/withhold-release-orders-and-findings.

14 The company’s e-mail address is no longer available and no one answers the phone number that is linked to the company. Google searches show that the company is “permanently closed,” although its status with the Public Registry of Commerce remains open.

15 “DHS/CBP/PIA-017 Non-Intrusive Inspection Systems Program,” CBP, June 2021, www.dhs.gov/publication/non-intrusive-inspection-systems-program.

16 “Non-intrusive Inspection (NII) Technology,” CBP, May 2013, www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/nii_factsheet_2.pdf.

17 “DHS/CBP/PIA-017 Non-Intrusive Inspection Systems Program,” CBP, June 2021, www.dhs.gov/publication/non-intrusive-inspection-systems-program.

18 “Non-intrusive Inspection (NII) Technology,” CBP, May 2013, www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/documents/nii_factsheet_2.pdf.

19 “Truck Carrying Dead Migrants Passed Through U.S. Checkpoint,” The New York Times, 29 June 2022, www.nytimes.com/2022/06/29/us/texas-migrants-deaths-truck.html.

20 “Peters and Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Improve Screening of Vehicles and Cargo at Ports of Entry,” U.S. Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, July 2022, www.hsgac.senate.gov/media/majority-media/peters-and-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-improve-screening-of-vehicles-and-cargo-at-ports-of-entry.

21 “Peters and Cornyn Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Improve Screening of Vehicles and Cargo at Ports of Entry,” U.S. Homeland Security & Governmental Affairs, July 2022, www.hsgac.senate.gov/media/majority-media/peters-and-cornyn-introduce-bipartisan-bill-to-improve-screening-of-vehicles-and-cargo-at-ports-of-entry.

22 “Boletines estadísticos,” Gobierno de México, 2022, www.politicamigratoria.gob.mx/es/PoliticaMigratoria/CuadrosBOLETIN?Anual=2022&Secc=3.

23 Empower submitted freedom of information requests to Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Mexico to confirm the existence of agreements that facilitate the exchange of biometric data. Non-governmental organizations such as Access Now and R3D, which advocate for the digital rights of immigrants, have also denounced this recently. See: “Alerta migrante: tus datos biométricos pueden estar siendo intercambiados con EEUU,” Access Now, 10 January 2023, www.accessnow.org/acuerdos-datos-biometricos-migrantes.