Who’s invested in destroying the planet?

The climate crisis is driven by corporate profit-seeking, as it has been since the first oil booms centuries ago. Research shows that, as of April 2024, 57 companies are responsible for 80% of the world’s CO2 emissions since the 2016 Paris Agreement.

At Empower, we follow the money to track the companies and investors behind new and existing fossil fuel infrastructure as well as nefarious renewable energy projects. We also explain how greenwashing and false solutions to the climate crisis, which the corporate capture of the State has largely normalized, prevent us from achieving a just renewable energy transition. Our research contributes to and guides diverse campaigns in both the Global North and South, from local struggles against harmful pipelines to global initiatives to reduce carbon. We map out the physical infrastructure and complex investment vehicles that underlie fossil fuel dependence and belie the just transition.

Some examples of our recent projects, which span the globe, include:

- New oil and gas exploration in South America, including liquefied natural gas (LNG)

- Fast-tracked LNG export build-outs in the U.S. and Mexico

- Private equity acquisitions of entire pipeline systems in the Persian Gulf

- Coal and gas-fired power plants in North Africa

- Fossil fuel export infrastructure in Australia

Energy Finance in the Middle East and North Africa: Key actors and trends in fossil fuel dependency

The Middle East often finds itself at the center of global geopolitics. Israel’s deadly escalation of conflict with multiple actors in the region, which includes receiving military support from the U.S. and European allies, led to humanitarian crises in Gaza and Lebanon, while pulling regional governments into a whirlpool of military posturing and political uncertainty.

While the stakes are higher than ever, the region’s centrality to geopolitics is not new. This has much to do with its place in international fossil fuel markets: the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is home to an estimated 57% of the world’s proven oil reserves and 41% of natural gas reserves. The region therefore finds itself at the center of another crisis: the climate crisis. On the one hand, the region is projected to see greater average temperature increases than anywhere else; on the other hand, the continued extraction and burning of fossil fuels in MENA will continue to provoke deadly climate events on a planetary scale, irrespective of local consequences.

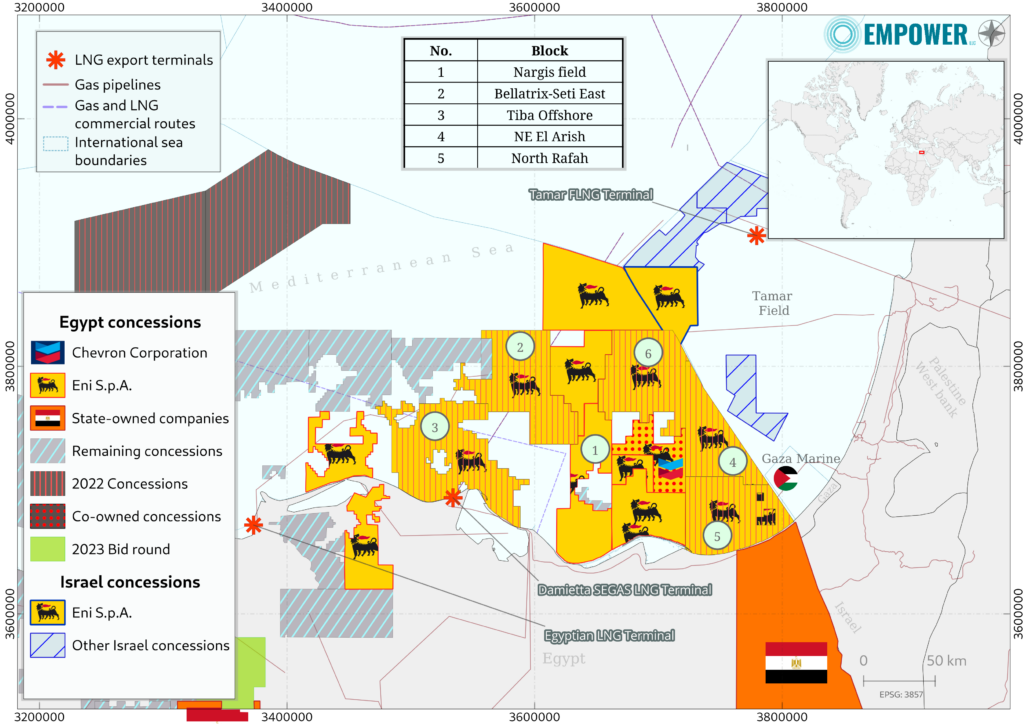

This map shows the concessions of Eni, an Italian energy company, in international waters near Egypt, Palestine, and Israel. It also shows Gaza Marine, one of the largest gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean and whose development is controversial, in international waters near Palestine.

In 2023, Empower conducted an in-depth investigation into the global financial flows and interests behind the MENA energy sector. Our report provided a nuanced picture of the key global actors driving fossil fuel dependency in MENA, beginning with the supposition that the global movement for a just transition to sustainable energy must be equipped with a complex understanding of these actors.

The report includes comprehensive data that can be used as a reference about different countries, sub-sectors, and thematic trends in financing. Additionally, several patterns and key financial actors emerge from the research, such as the region’s massive sovereign wealth funds; the rise of BlackRock as a financial power broker in the Gulf; the pseudo-privatization of entire national pipeline systems as a capital-raising mechanism; the greenwashing of fossil fuel bonds in Europe; and the growing importance of Islamic financial instruments for renewable energy.

The state of gas financing in Latin America and the Caribbean (2018-23)

Empower tracked investments in 83 strategic gas projects (upstream, midstream, and downstream) that were built, under construction, or about to be built between 2018-23 in nine Latin American countries.

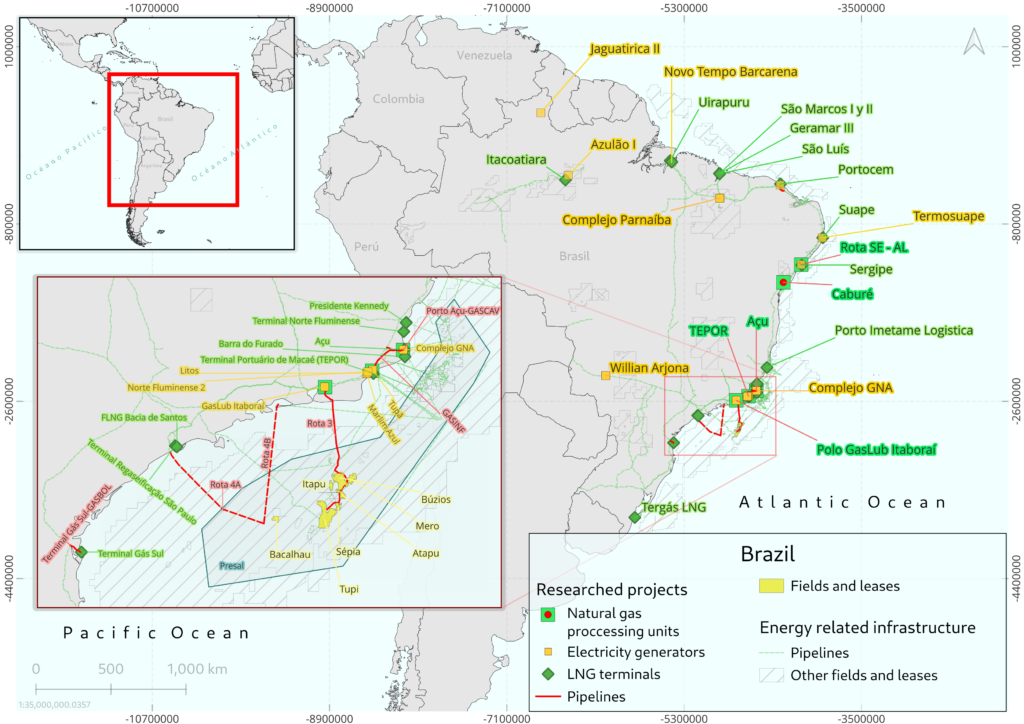

This map shows energy projects in Brazil as of August 2023, including pipelines, fields, and energy infrastructure.

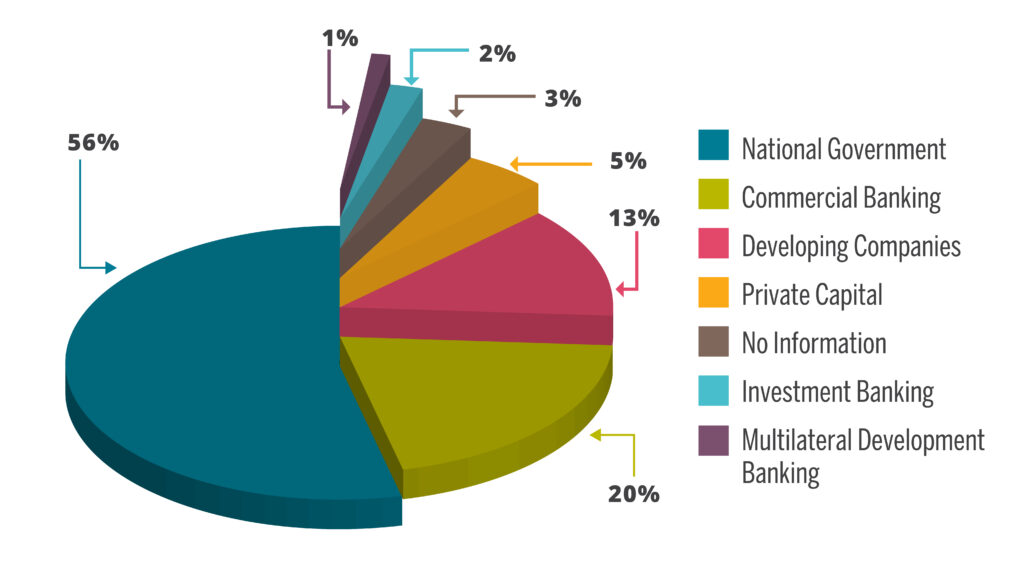

We identified 92,713 million USD of financing, which was allocated to gas projects by both the public and private sectors, as well as through public-private partnerships. These funds were transferred via debt, equity, and public fund allocations.

The main financing mechanism was the transfer of public funds through State-owned institutions, such as energy companies and Export Credit Agencies. In second place was commercial banking, which primarily participated through the provision of debt. In third place were the developers, meaning the energy companies themselves, which financed projects through their balance sheets without issuing specific project debt.

Gas project financing in Latin America by type of institution (2018-23)

Source: Empower, 2024.

The report “Mapping Gas Financing in Latin America and the Caribbean (2018-23)” provides a panoramic view of the specific needs of gas projects in each of the studied countries, as well as the entities and countries financing these projects. The full report is only available in Spanish.

In the downloadable document you will find a summary of the key findings of the report. This information is strategic for civil society actors opposing project development or advocating for corporate accountability in gas projects in their countries, especially because it helps to hold accountable the governments and private entities financing these projects.

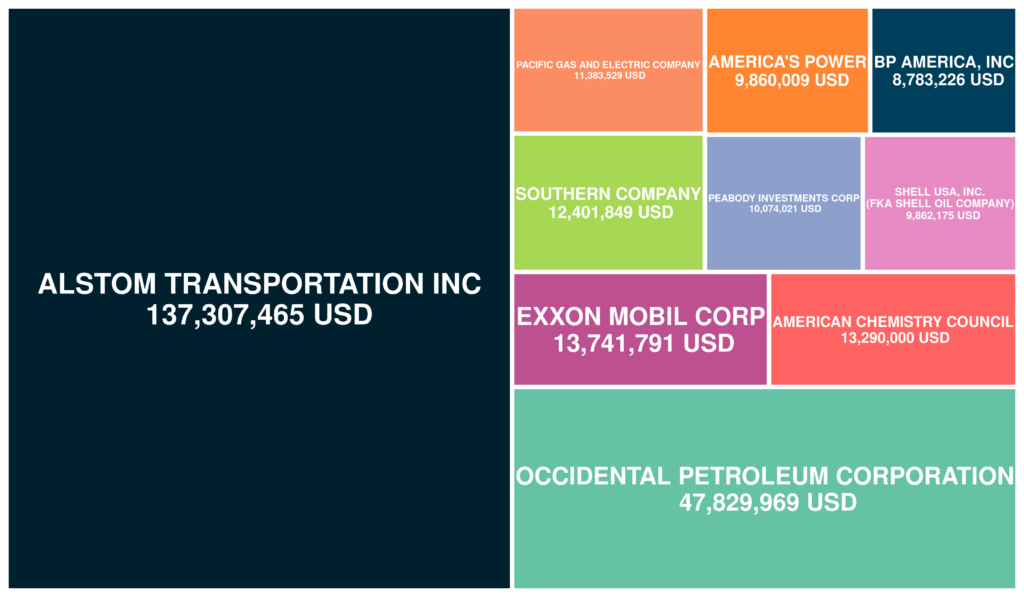

Carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) in Texas

Major climate legislation passed during the Biden administration in the U.S. will provide billions of dollars in new subsidies and financing for carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) projects. This false solution to the climate crisis was heavily lobbied for by fossil fuel companies that aim to use CCS as an excuse to extend the extraction of oil and gas for many years to come. However, the technology has proven to be a technological flop that does not capture anywhere near the promised quantities of greenhouse gas emissions, while threatening to pollute communities with underground CO2 leaks and endangering the public with CO2 pipeline explosions that regulators and emergency responders are unprepared to handle.

From November 2023 through April 2024, Empower conducted a comprehensive mapping of CCS projects in Texas, as well as research on their financing. Together with Louisiana, where we recently carried out similar research, these two states along the Gulf of Mexico will be the epicenter of CCS development, often in communities already devastated by industrial pollution. In both, we found that CCS projects will be overwhelmingly financed with federal grants and tax breaks structured as subsidies — meaning that the public will fund CCS by directly paying companies like ExxonMobil and Occidental Petroleum.

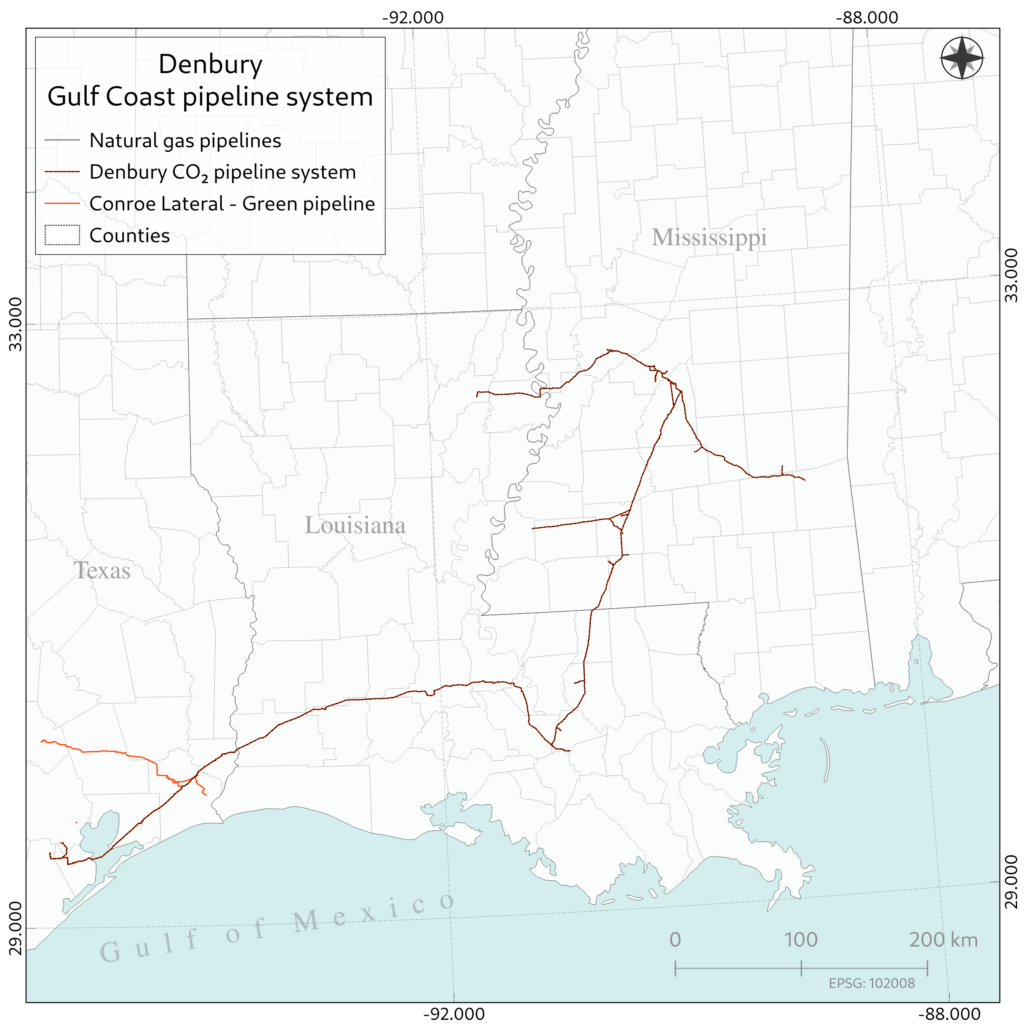

This map shows the CO₂ pipeline routes owned by Denbury, which was acquired by Exxon in 2023.

Exposing human rights violations and socio-environmental conflicts in the automotive supply chain

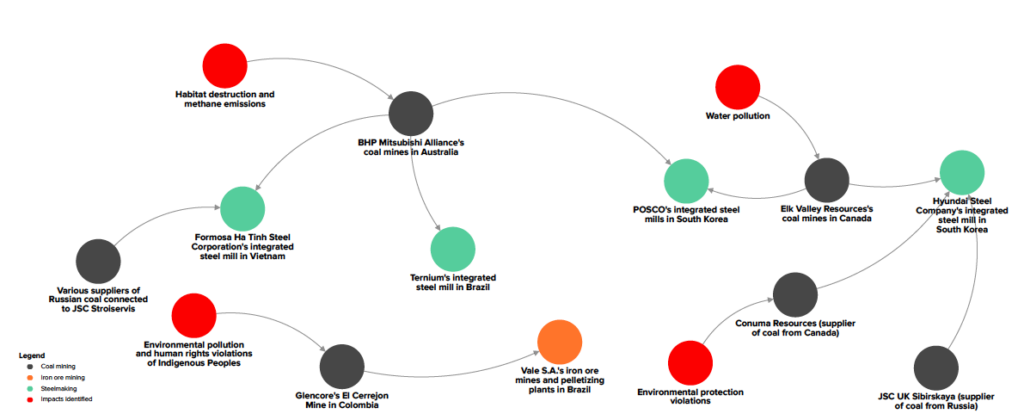

Steel manufacturing is the largest contributor to global greenhouse gas emissions among industrial sectors, with the automotive sector ranking as the third-largest user of steel worldwide. As a major consumer of fossil-intensive materials, the automotive sector holds significant responsibility for these emissions, but also plays a crucial role in driving the energy transition. In 2024, Empower collaborated with several partners to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the global steel supply chain of Hyundai Motor Company — the world’s third-largest automaker and the only one with its own steel-making subsidiary, Hyundai Steel Company. Despite Hyundai’s claims of leadership in electrification and sustainability, our research uncovered a series of severe impacts on local communities and the environment throughout its supply chain.

Iron ore miners identified in Hyundai’s supply chain

We traced Hyundai’s steel supply chain from iron ore mines in Brazil and metallurgical coal mines in Australia and Russia to steel-making facilities in Mexico, South Korea, the United States, and Vietnam. These facilities supply materials that are ultimately used to manufacture Hyundai and Kia vehicles, which are distributed and sold in markets around the world. Throughout this supply chain, we identified and examined operations linked to significant climate and environmental damage, as well as human rights violations, many of which remain unresolved. Hyundai has a unique opportunity to strengthen human rights due diligence, decarbonize its steel supply chain, and accelerate its transition to electric vehicles. Without immediate and decisive action, however, its sustainability narrative risks becoming yet another flagrant example of greenwashing.

How do we track who’s behind fossil fuel infrastructure?

We start by following the money. Using a range of proprietary databases, as well as open-source and government data from around the world, we reverse engineer and unravel the financial flows enabling fossil fuel projects. Sometimes, we look for specific actors; other times, we identify sector-wide investment trends, and so on.

These investigations lead us to analyze all of the economic inputs and policy decisions upon which the fossil fuel economy relies, such as:

Trillion-dollar asset managers

Pension fund investment criteria

Corporate bond and green bond emissions

Bank loans

Government subsidies

Permit issuance

Corporate deal-making

Energy transition targets

Lobbying paper trails, and countless other puzzle pieces

This graphic shows the top companies that lobbied the U.S. Congress for pro-carbon capture legislation. The name of the company and the amount spent are displayed.

Climate financing and false solutions

Our research also covers the growth of green energy financing and its complex considerations. For example, hydrogen fuel and carbon capture and underground storage (CCUS) do not present viable alternatives to fossil fuels. Our research has shown that their biggest promoters are oil and gas companies looking to clean up their image as they pump more fossil fuels — all while risking massive groundwater contamination, ocean acidification, and deadly CO2 pipeline explosions.

Meanwhile, viable technologies such as wind, solar, and hydropower projects can present problems of their own. Project developers, particularly in the Global South, have committed human rights abuses and assassinations of human rights defenders. When required, we also track down the web of interests behind these crimes to help local advocates and loved ones seek accountability and justice.

A just transition that prioritizes people and planet

Green developers must respect human rights, including the consultation and consent of affected communities, as well as rigorous environmental impact studies and regulatory compliance. That said, words are cheap and so are rubber-stamped approvals in many jurisdictions. Our research gets to the bottom of the power relations that underlie green infrastructure, because we know that, just like with fossil fuels, following the money is key to understanding whose interests will be protected — and whose will not.

The stakes could not be higher. That’s why we collaborate with front-line social movements, CSOs, and campaigners to dig up information that helps them protect communities and workers during the energy transition and win back our planet from corporate interests.